I recently sent a presentation to a conference on 3D printing called Going for Gold: 3D Printing, Jewellery and the Future of Intellectual Property Law (unfortunately I couldn’t attend in person). Hosted by Professor Dinusha Mendis and Professor Maurizio Borghi, the conference had an all-star line-up, bringing together experts from the cultural and business sectors including designers, manufacturers, distributors, policymakers and legal professionals. If you’re not familiar with the Going for Gold case study, you should be. The project explores copyright, design, and licensing issues surrounding 3D scanning, 3D printing, and mass customization of ancient and modern jewelry in the cultural and business sectors.

My presentation summarized how my theory of Surrogate IP Rights applies to the topic of 3D surrogates. For the post, I’ve broken the slides and text down into modified images and narrative below; so here it goes:

Left image downloaded from: http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/works-in-focus/painting/commentaire_id/tahitian-women-16715.html?cHash=503c89d7d8; right image is the museum’s digital surrogate printed to the dimensions of Paul Gauguin’s painting and subsequently photographed

First a bit of terminology. Underpinning my research is the notion that (the majority of) reproductions of artworks do not attract a new copyright because they do not meet the threshold of originality as required by copyright law.

These reproductions serve as surrogates for the original work. Today, this is usually a “digital surrogate”, a term used in the Getty Museum’s Open Content Images Policy (scroll down to “Public Domain and Rights“). When a digital surrogate is made material again, such as when printing 2D or 3D data, it produces a “material surrogate” for the artwork—something that also does not meet the threshold of originality and is a copy.

Left screenshot taken from: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hockney-george-lawson-and-wayne-sleep-t14098; right screenshot taken from: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-ophelia-n01506

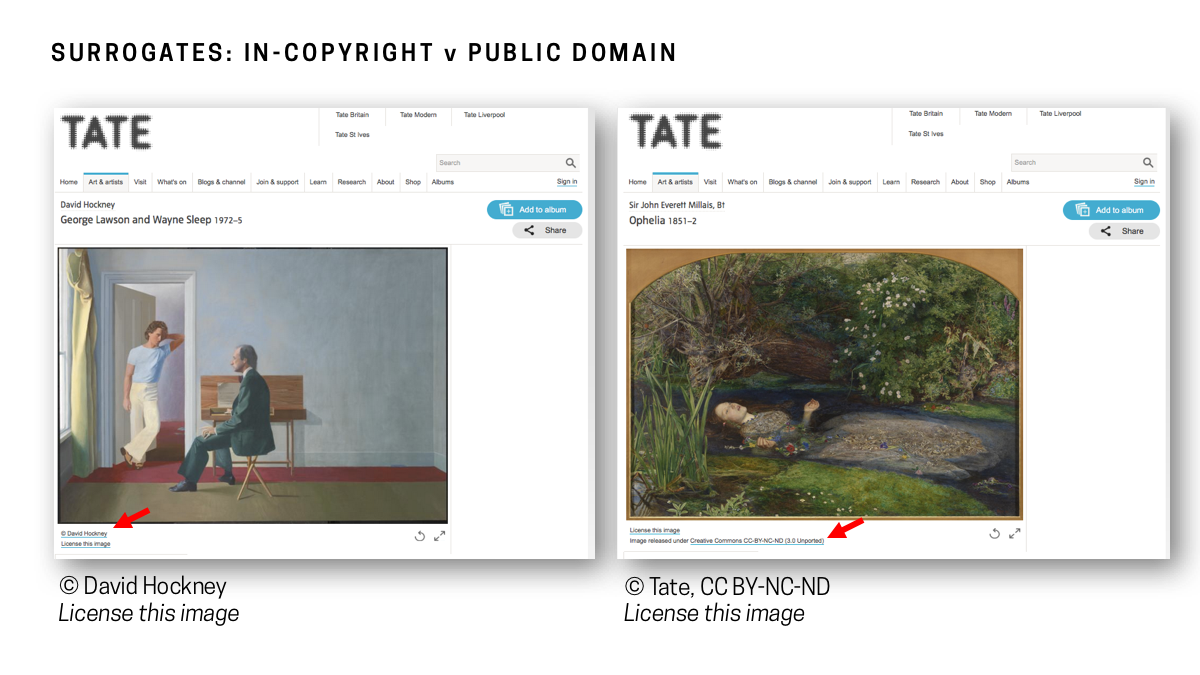

Interestingly, institutions treat surrogates differently when the material object is in copyright versus when it is in the public domain. For example, on the left is a reproduction of a work by living artist David Hockney, which is clearly marked © David Hockney, regardless of how or by whom it was made, as it is a copy of his in-copyright portrait.

By contrast, on the right is a reproduction of a work by Millais, who died more than a century ago, which is marked © Tate and released under a CC BY-NC-ND license. Millais’s painting is in the public domain. Yet, in this case, the same process of making a reproduction somehow produces a new original work, even though it is presented online as Millais’s work.

A game! A game!

So, to put this into context, name this artwork in your head. Easy, right?

You’re probably thinking it’s the Mona Lisa.

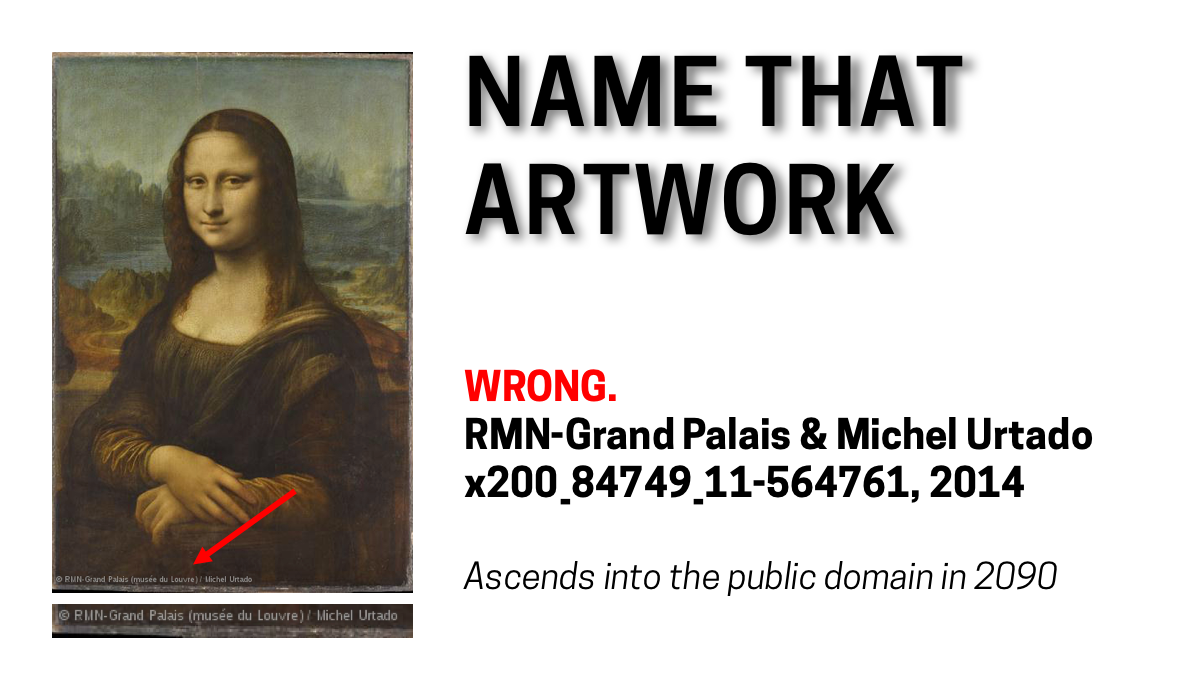

But you’re WRONG.

Admit it. You lost.

This is an original RMN-Grand Palais & Michel Urtado.

It’s titled x200_84749_11-564761 – And, according to its metadata, it was created in 2014.

That means this image will ascend into the public domain in 2090, when we will all be dead and no one will be using low resolution images.

‘Crowd looking at the Mona Lisa at the Louvre,’ by Victor Grigas, CC BY-SA 4.0, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40250423

This has so many repercussions for the public domain.

To be clear, the issue isn’t that the Louvre has taken the Mona Lisa and monetized it. Works in the public domain are fair game to anyone to monetize, including cultural institutions.

The issue is the threshold of originality required by law to attract a new copyright has not been met. And in saying that it has, the museum is signaling to users that its reproduction is a new original work by the museum while presenting it to users as a work by someone else.

But for argument’s sake, let’s say that copyright is valid. In theory, what is fair for cultural institutions should be fair for everyone else. Meaning, anyone could visit the artwork, make a reproduction and claim a copyright.

But in reality, a visitor is bound by the Louvre’s visiting rules, which restrict use of photography taken inside the museum space strictly to private use of those photos outside of the museum space.

The combination of these restrictions creates a monopoly around our common cultural heritage in the public domain. And it conflates the rights in property with rights in intellectual property.

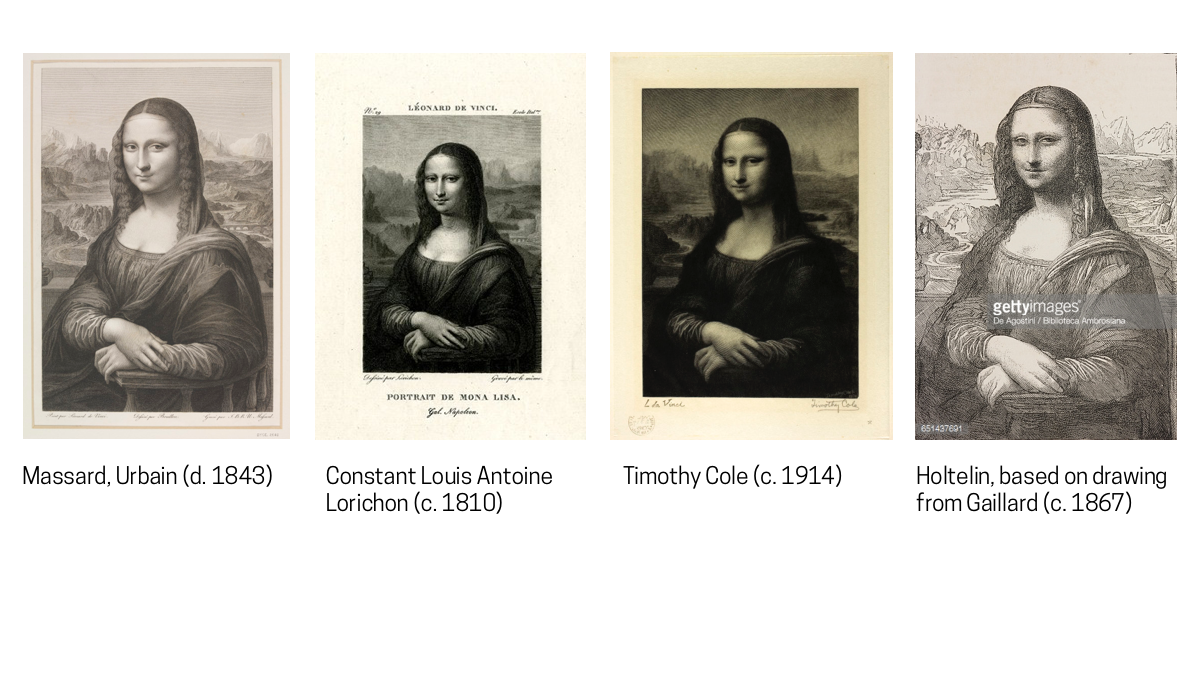

From left to right: Massard; Lorichon; Cole; Holtelin, based on Gaillard

Of course, today most reproductions are digital, made with photographic technologies. But surrogates were originally made by hand. Often, the maker had no access to the original work, which is the case with the print on the very right: it’s a Holtelin, which is based on a drawing by Gaillard. So, in other words, this print is a surrogate of a surrogate.

At the height of reproductive printmaking in the late nineteenth century, engravings might be seen in one of two ways: either as an interpretive engraving or as a facsimile engraving, a work which still took an incredible amount of time and skill to produce, but was not viewed as a creative production for a number of reasons (more on this in my PhD dissertation).

Luckily, the surrogates above were created so long ago they are now in the public domain, unlike the Louvre’s digital surrogate of the Mona Lisa…

except that they’re not:

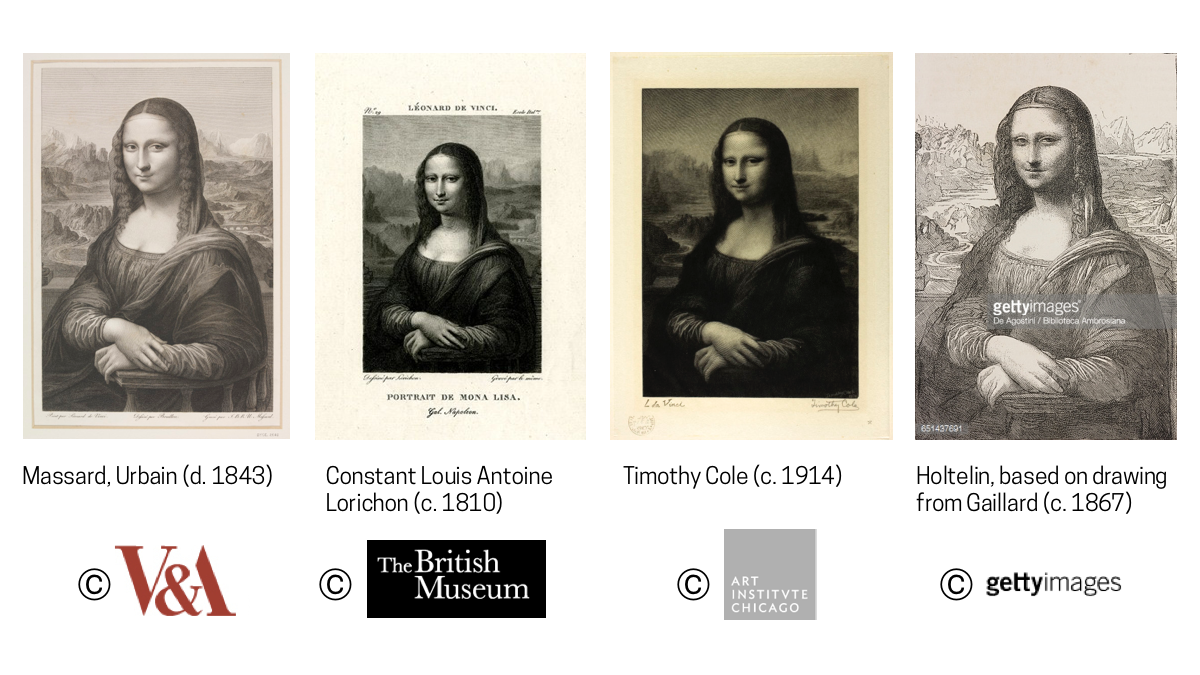

From left to right: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London; © Trustees of the British Museum; © The Art Institute of Chicago; © Getty Images

Instead, each is restricted by a copyright claim. As technologies continue to progress, this practice has the effect of locking up the public domain in perpetuity.

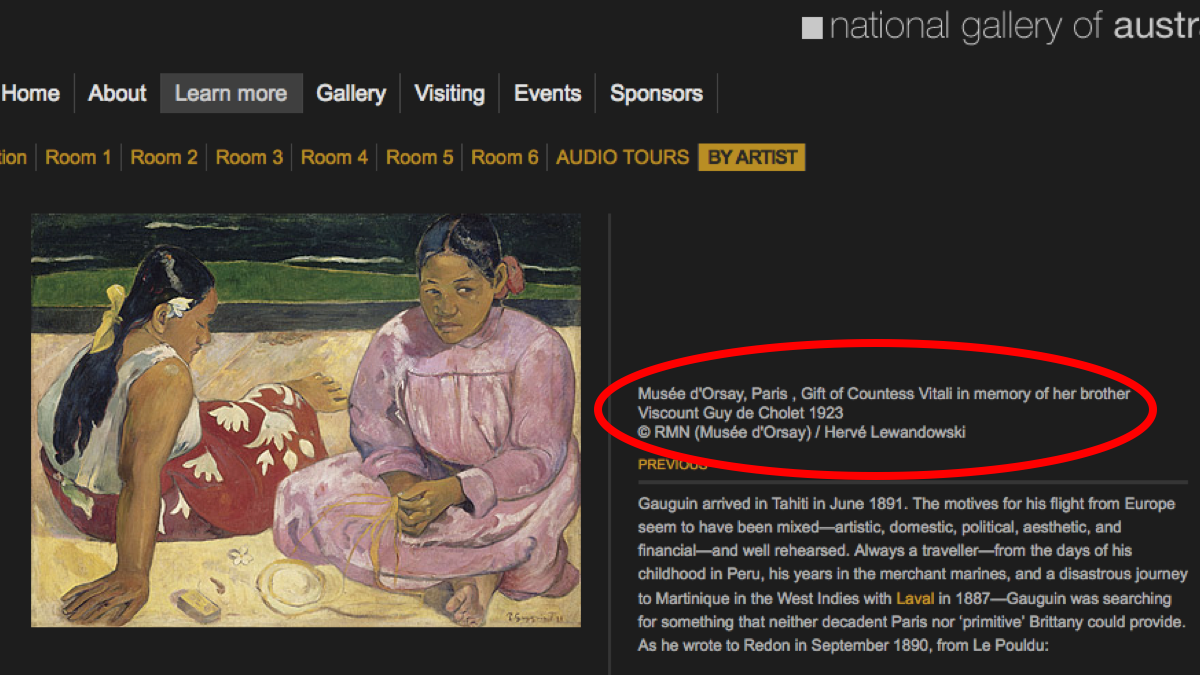

Screenshot taken from: http://nga.gov.au/Exhibition/MasterpiecesFromParis/Default.cfm?IRN=191205&BioArtistIRN=21810&mystartrow=61&realstartrow=61&MNUID=3&ViewID=2

This is something explored by a recent project I worked on with Professor Ronan Deazley of Queen’s University.

With all of this in mind, Ronan and I set out to learn what might happen if we looked at institutions as the authors themselves, and especially if we removed entirely the context of the original author and artwork (see how Paul Gauguin’s information and title for the work has been removed above)?

More importantly, could we learn anything about the claim, legitimacy, or exercise of intellectual property rights over surrogates in the process?

Photograph taken of the gallery opening, © Michael Gimenez, CC BY

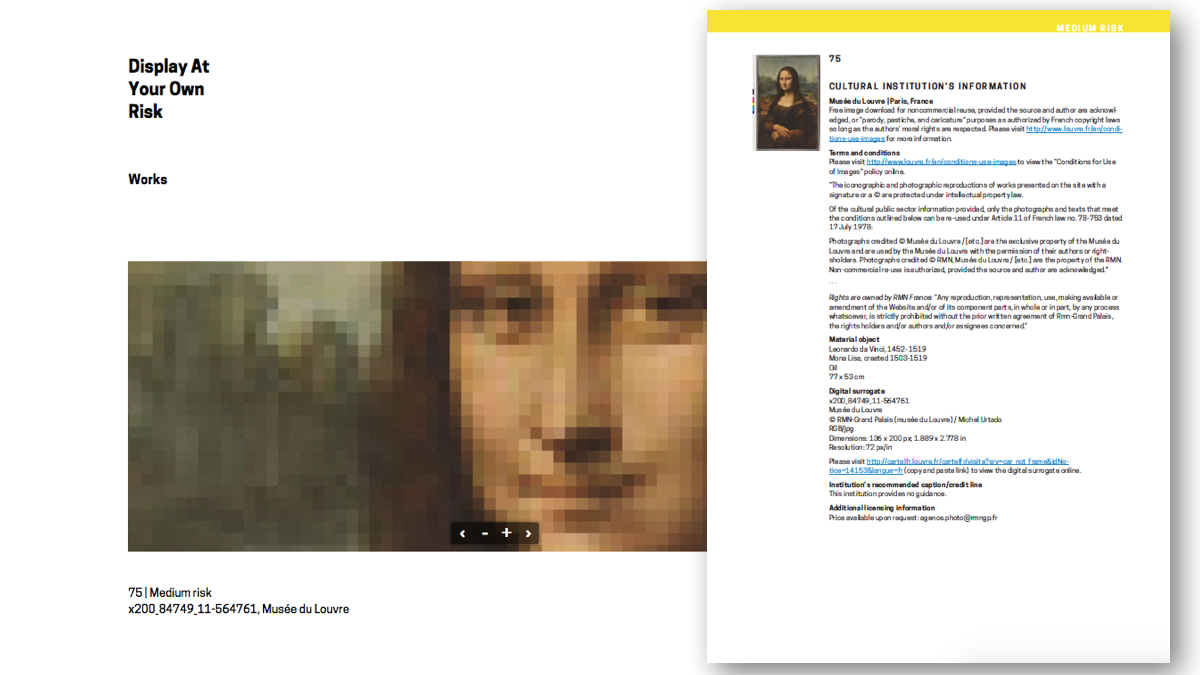

Display At Your Own Risk is the natural result of these questions.

Its a research-led exhibition experiment featuring digital surrogates of public domain works of art produced by heritage institutions of international repute.

It examines the path a public domain object takes during digitization and challenges whether a work’s status—and authorship norms—should change simply through the creation of a digital version, which is viewed by the institution as a new and independent asset.

We visited various institutions’ websites, downloaded recognizable works, printed them to the dimensions of the material object, and hosted an exhibition of works by cultural institutions.

The www.displayatyourownrisk.org website with an example of the reproduction information provided with each digital surrogate in the open source exhibition file.

We also digitized the prints, organized them into categories of risk in reuse (i.e., no risk / open; low risk; medium risk; and high risk) and made everything available online as an open source exhibition. Users can download the file, which has all the components necessary to host an exhibition, including information about each institutions’ rights and reuse policies.

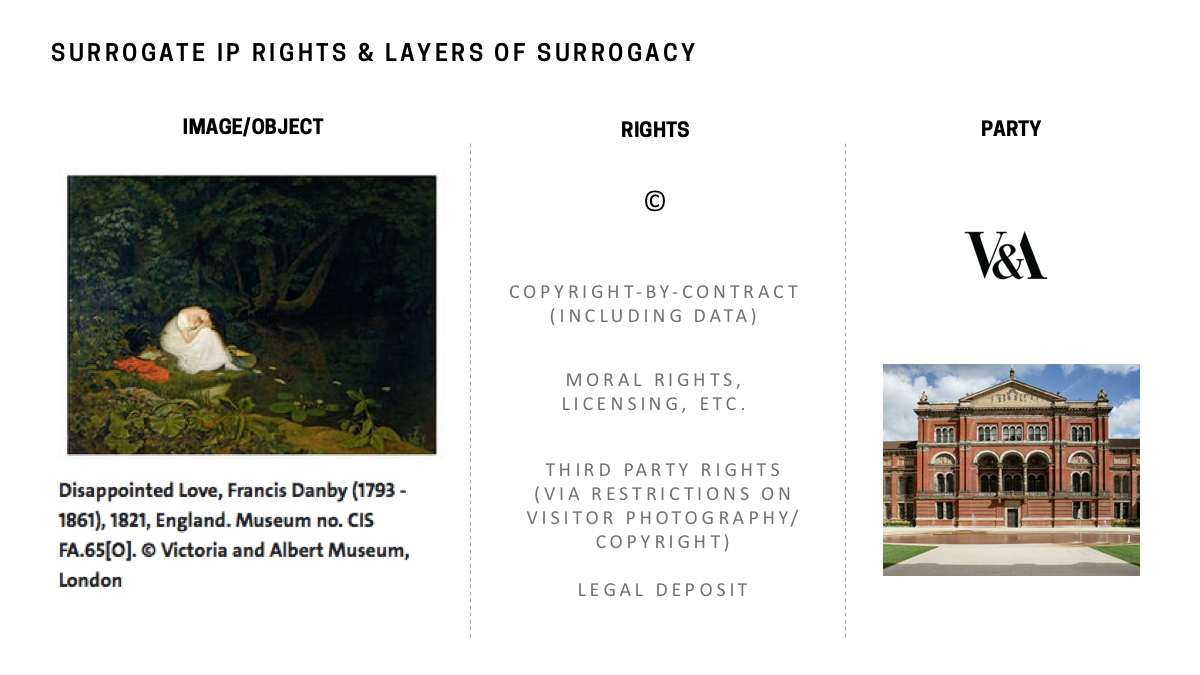

Layers of surrogacy apply to the image/object, the rights claimed, and the party or author making the claim.

This brings me to the theory that underpins my thesis. I use the term Surrogate IP Rights to refer to intellectual property rights claimed over surrogates – either outright through a copyright or through the terms and conditions of the website or the image license.

Surrogacy, itself, applies in different layers. First, the image is a surrogate for the material object. In this case, it’s Danby’s Disappointed Love. The museum cites it as so and presents it as Danby’s own work. The true value of the image lies in the underlying material, and it is cropped exactly to its dimensions. Just underneath, however, is © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the actual maker of the surrogate. The institution holds and controls access to both the material object and its digital surrogate, which creates tensions with the rationale behind the public domain and the creation of new cultural goods.

What results are Surrogate IP Rights. The copyright in the material object has expired, and sometimes never existed in the first place; thus, this new claim to intellectual property steps up and stands in place of any previous claim. These claims to rights include surrogate copyright and copyright-by-contract (including over data or other material which is normally non-original and not protectable), surrogate moral rights and licensing, surrogate third-party rights through restrictions on visitor photography which operate as a third-party copyright in the visitor’s photos, as well as a surrogate legal deposit when the institution requires a user to deposit a copy of his or her use (such as in a publication) with the institution.

And they are claimed by a surrogate author or party, which in this case is the V&A.

On top: #NEWPALMYRA; on bottom: CyArk.org

Nor surprisingly, users and the private sector are responding much faster to the direction surrogates and openness are taking.

One example is #NEWPALMYRA, which recreates lost cultural heritage sites in Syria and releases the data online. All content is open access and open source. The website operates under CC0, which is displayed on every webpage. Users can make their own contributions via GitHub, all of which are subject to CC0.

Another example is CyArk, which laser scans cultural heritage sites for preservation. Most online content is available to the public at no charge for non-commercial, educational use. Some have CC licenses. And there are many, many other examples in addition to these.

So, it could be that this trend of relinquishing copyright or at least relinquishing many of its benefits through the license is a solution to many of the automatic legal protections which conflict with the projects’ missions.

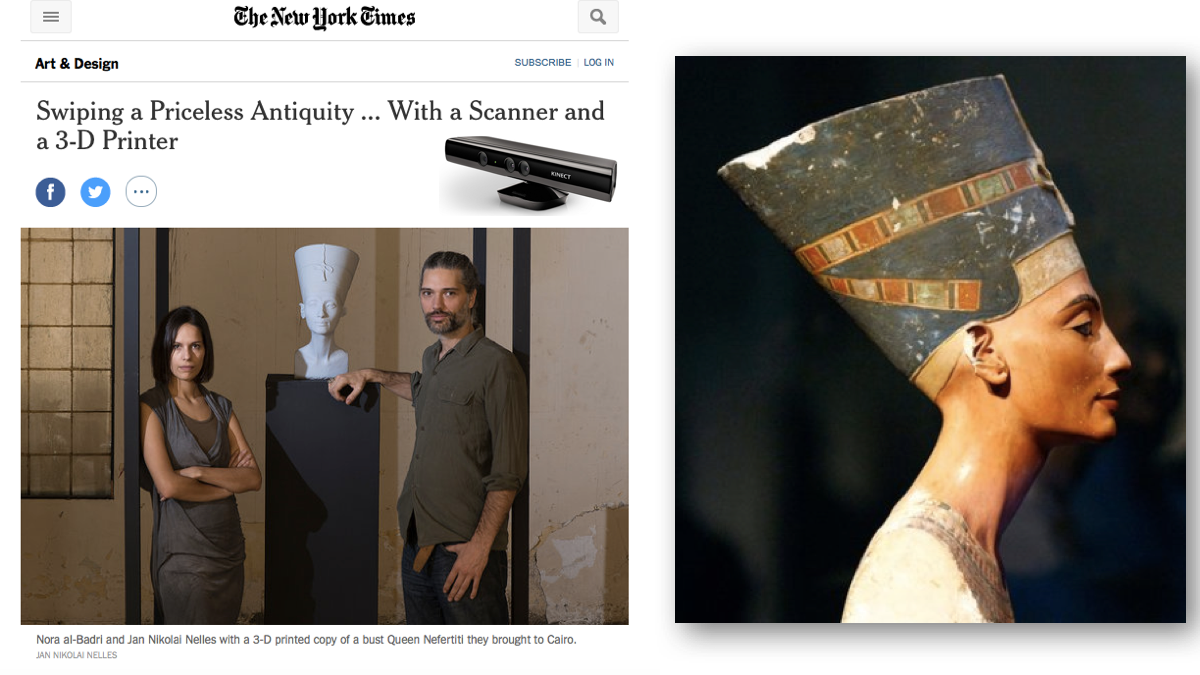

On left: screenshot from the New York Times article, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/02/arts/design/other-nefertiti-3d-printer.html?_r=0 and a photo of the Microsoft Xbox 360 Kinect camera; on the right, the bust of Nefertiti

And, last year (get ready, this is my favorite thing ever), two German artists, Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles, visited the Neues Museum in Berlin and allegedly made a scan of the bust of Nefertiti with a Nintendo Kinect camera, used it to create data of the object, and released the data online.

A video released by the artists shows the camera was hidden beneath a scarf…

Still from the video

… and pulled aside to scan the bust as one of the artists circled the work.

Still from the video

The bust is in the public domain so there are no copyright concerns; however, they violated the terms of visitor photography, specifically the part that says:

The written permission of the museum management board is required to show film footage and photographs taken in the museums for commercial purposes of any kind. The museum management board also has the right to impose a general ban on photography in exhibitions and exhibition rooms.

And at one point in the video we can even hear a member of museum staff saying, “No photos, please.”

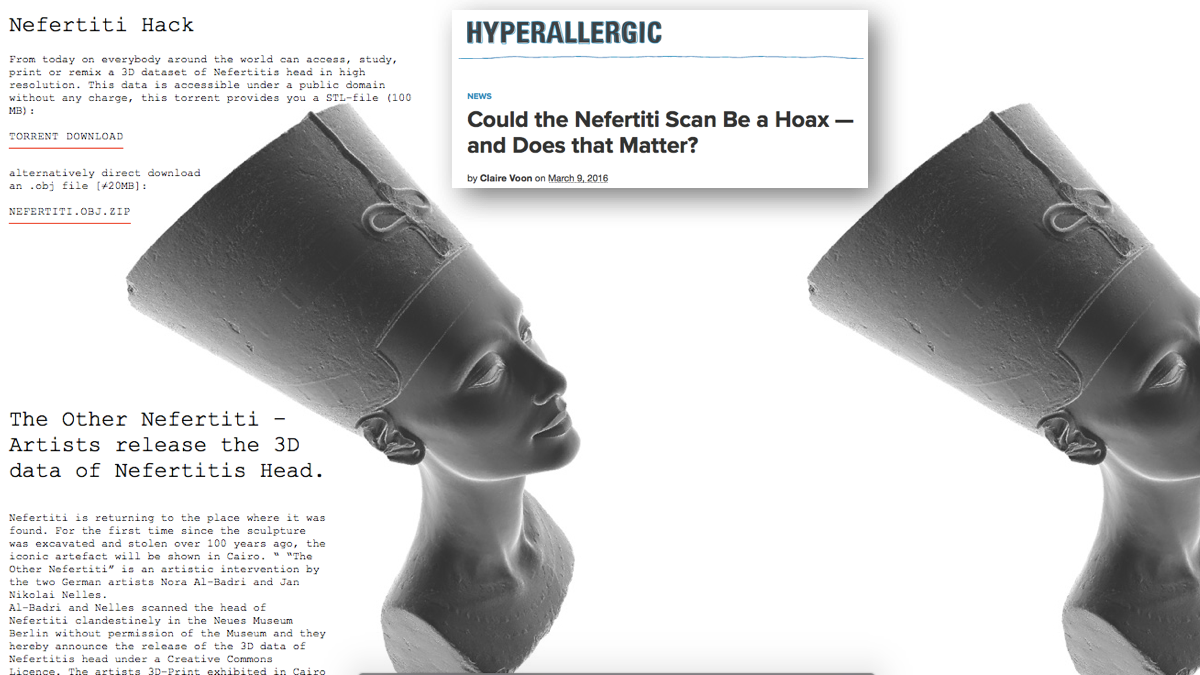

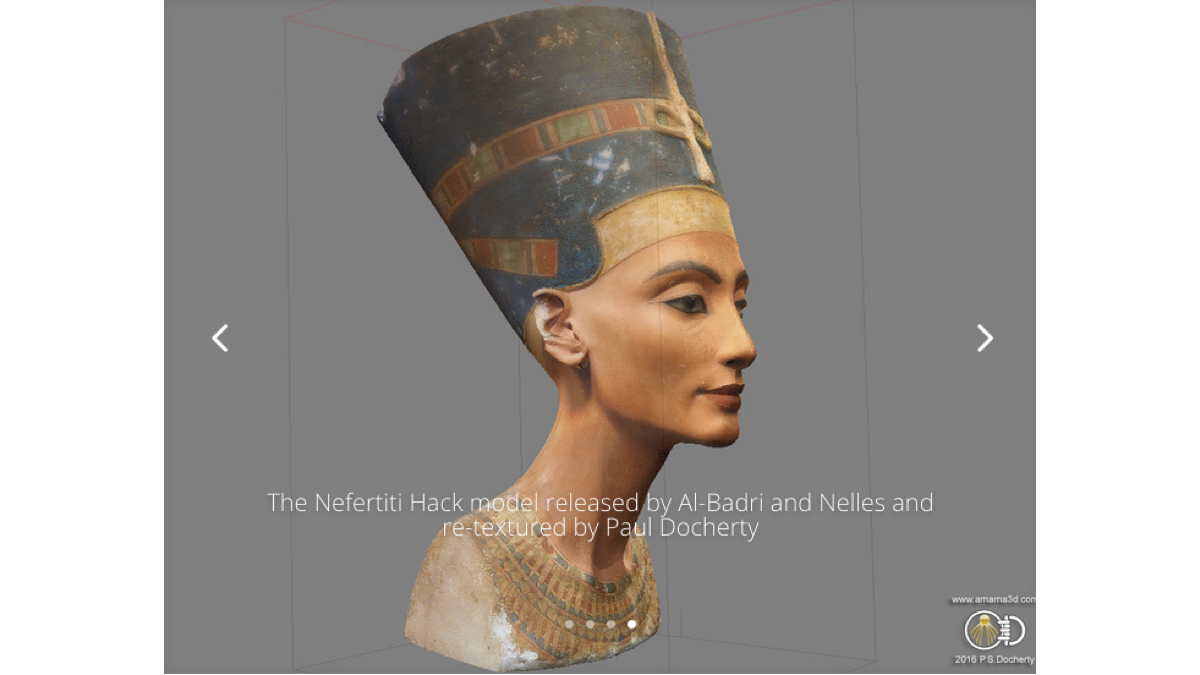

Nefertiti Hack: http://nefertitihack.alloversky.com/

But, many who have analyzed the data say it’s *extremely* unlikely the camera and process they used could have produced such a detailed scan of the bust.

The issue has produced some controversy, with people calling it a data hack instead of an art hack, but people are also asking, “Does it really matter?”

[Side note: I find it extremely interesting that the rhetoric surrounding the debate refers to the project as a possible “hoax” and depicts it as an “art heist.” Consider this against the backdrop of how the artifact came to be in the possession of the Germans in the first place and the Egyptian Government’s position that it had been “looted” from Egypt.]

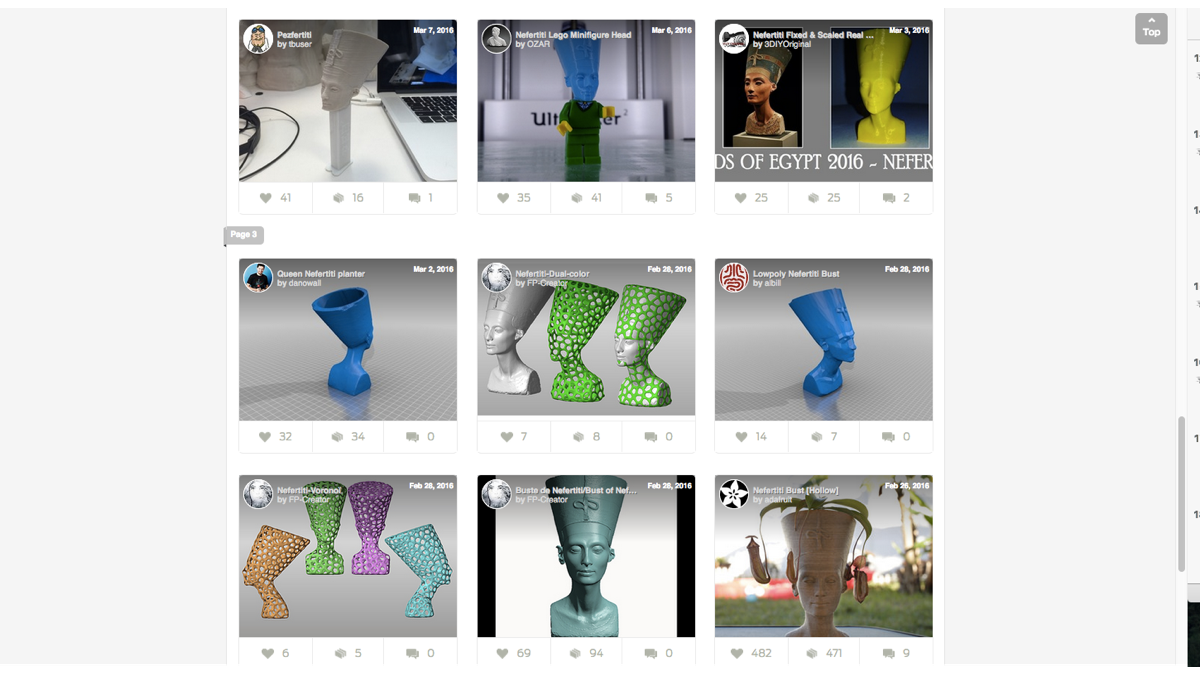

Thingiverse webpage for works tagged “Nefertiti”, https://www.thingiverse.com/tag:Nefertiti

The data has been downloaded and remixed by the public for jewelry, Pez dispensers, Lego accessories, and potted plant containers…

The Nefertiti Hack model released by Al-Badri and Nelles and re-textured by Paul Docherty

And even retextured and rereleased for the purposes of study.

So, in this instance users have filled the gap left open by the museum. You can imagine the museum wasn’t too happy.

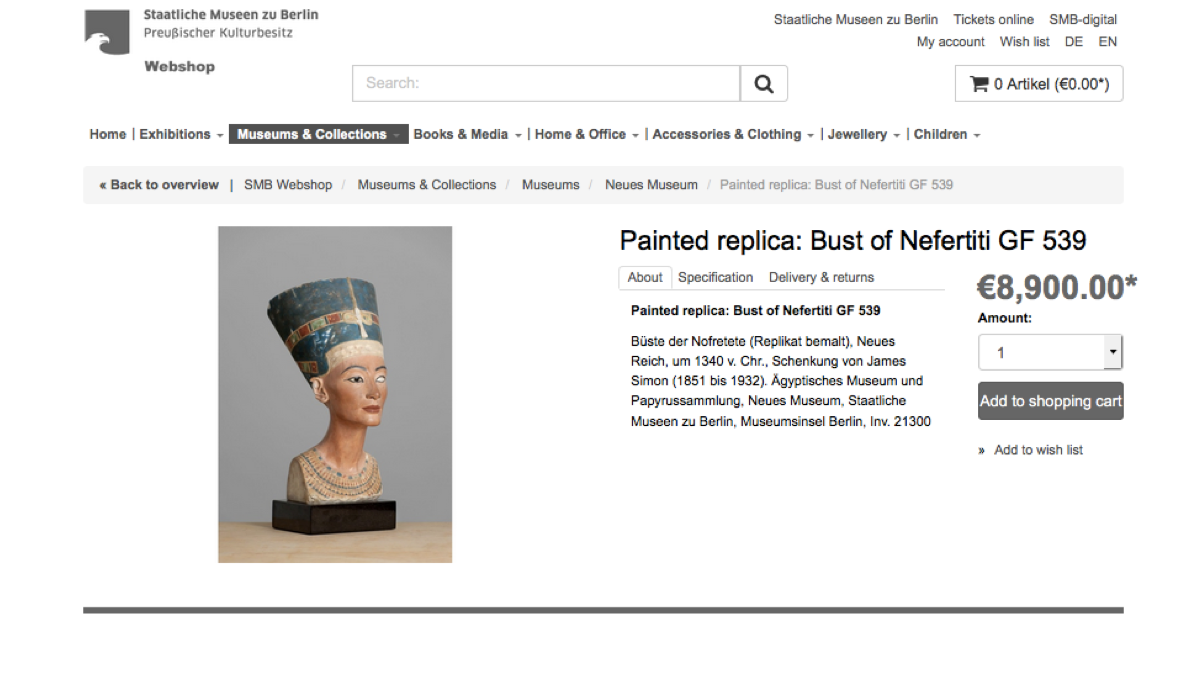

Webshop for the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin’s Painted replica, https://www.smb-webshop.de/en/subjects/nofretete/2502/painted-replica-bust-of-nefertiti-gf-539?c=101031

One of the reasons people suspect the museum is upset is because it sells a limited edition painted replica of the bust online for about 9,000 Euro excluding VAT, which it made through its own 3D scans of the bus. And some people speculate the artists might have obtained a copy of this data rather than making it themselves.

Photo from a visit to the Victoria and Albert Museum last summer. I claim no copyright in this non-original photograph, however I violated the V&A visitor photography policy (see below).

But 3D surrogates as an object of study have always been a thing. In the nineteenth century, plaster casts were made from molds of the original works and widely offered for sale by institutions; all major museums and art schools had casts for study and art education. Even today, the V&A has entire galleries dedicated to display of the high-quality surrogates in its collection.

[Side note: I claim no copyright in the photo above, a snapshot I quickly caught with my iPhone while strolling through the V&A’s gallery of 3D surrogates, which I published to Twitter and then again on this blog. However, I’ve apparently done this in violation of the visitor photography policy, “Access and Photography of V&A Collections and Exhibitions“, which reads:

1. Photography of V&A Collections and Exhibitions

Objects in the collections may be photographed by visitors for private study, educational and non commercial research purposes only, as agreed in advance with the curator. Any photographs or videos taken in the Museum are for personal use only and may not be published. Commercial use of any kind is not permitted.

Oops, sorry everybody. This policy was posted only online, and not anywhere at the museum during my visit. So how could I have known? (But, really?)

The future of surrogacy: The Virtual World Heritage Lab *swoon*

But we all know 3D surrogates today are no longer simply casts or representational data.

The Virtual World Heritage Laboratory (VWHL), at in the Indiana University has formed a partnership with the Uffizi Gallery to digitize in 3D its entire collection of Greek and Roman sculptures. Totaling around 1,250 works of art, it is the third largest collection of its kind in an Italian state museum.

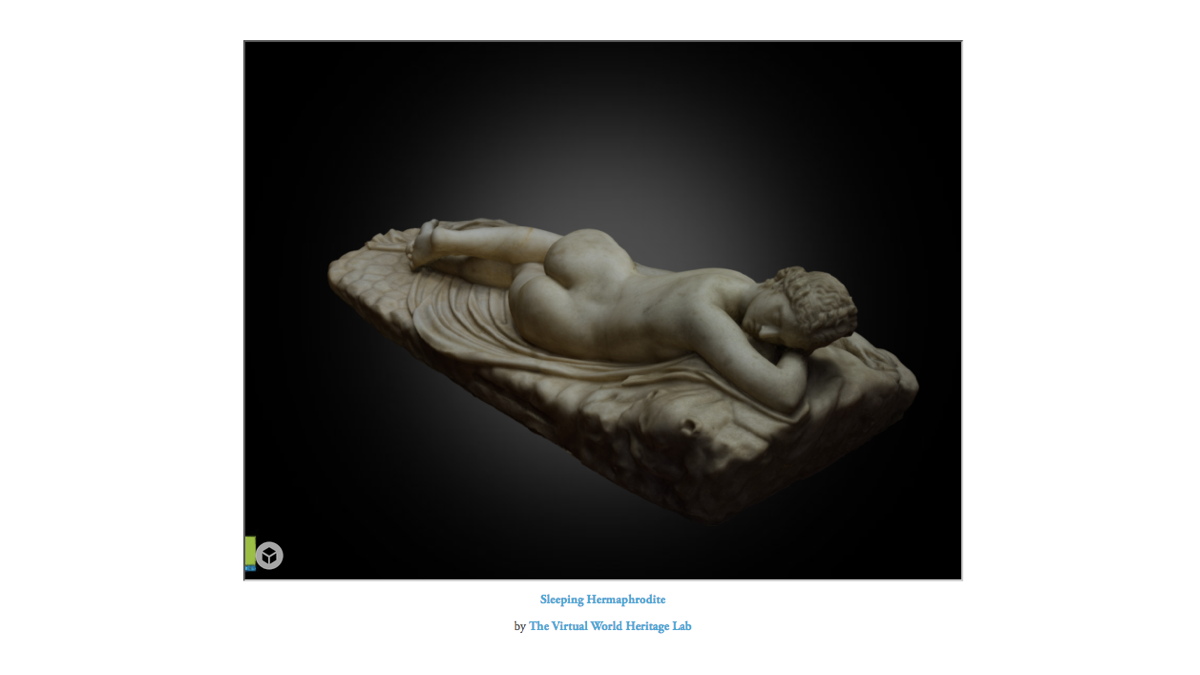

Virtual surrogate of Sleeping Hermaphrodite at the Uffizi Gallery, from the Virtual World Heritage Laboratory, http://vwhl.squarespace.com/uffizi-project

The virtual surrogates will be made available online through the Laboratory and the data will be used to make material surrogates which will be extended for loans. The project also plans to virtually restore many of the works to how they might have originally appeared when made, applying virtual paint using virtual methods of application from its period to create virtual originals (*mind blown*).

So you can see how copyright might apply – or not – to various layers of the data comprising these virtual surrogates. And this is the direction surrogacy is going.

Photo from Van Gogh Museum, Relievo Collection, https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/business/relievo-collection, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Even with 2D works.

Last year, the Van Gogh Museum worked closely with Fujifilm Belgium to develop an innovative technique combining an accurate 3D scan of the painting with a high-resolution print. They’re reproducing works in a limited edition called the Relievo Collection and offering them for sale. (Rumor is they’re priced around €30,000. I would love)

And online, the Museum touts: “The reproductions are of such high quality they are almost indistinguishable from the originals.” Where the legal assessment for a new copyright turns on “originality”, you can see how this becomes problematic. And with developing technologies it will only become more complicated.

The Washington Post article, “This is how you photograph a million dead plants without losing your mind”

This is why it’s so important we settle the issue at its most basic level.

This Washington Post article from February is titled “This is how you photograph a million dead plants without losing your mind” and it details how digital technicians literally hear the beeps and whirs of the Smithsonian’s conveyor belts in their dreams at night. You can watch a video online here, and I quote:

At the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, three young museum scientists have taken on the mind-numbing but important task of the digitizing millions of dried plant specimens. This is what it’s like.

* Enter beeping and whirring sounds for almost two whole minutes *

The absence of originality is not simply due to the use of conveyor-belt technology. Instead, and this is true throughout the industry, creative choices are being limited in many other ways – by industry-made best practices, by digitization guidelines and standardized methods, by the lack of choice of which technologies are available due to what is provided by the institution, by the lack of choice in subject matter and representation, and so on.

[Side note: the Smithsonian’s general policy is to not claim copyright in reproductions of public domain material, but instead to restrict reuse to personal, educational, and non-commercial purposes through its terms of use. In many cases, however, the Smithsonian makes content available for all types of use, including commercial.]

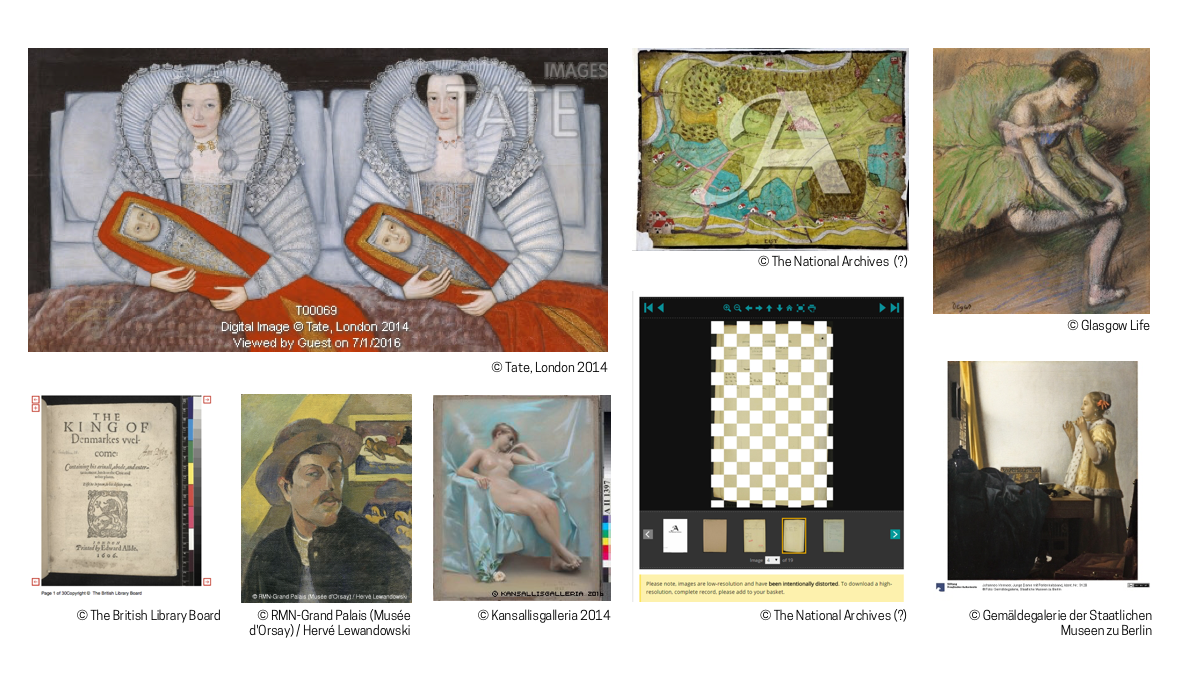

Only a few examples of rights information being imposed over the image, in some cases prohibiting access entirely.

It’s time accept the fact that owning a work does not mean owning its copyright.

Still, going open doesn’t mean that an institution must give its reproductions away for free (If only that were possible in every case, right? But it’s not.). Reproductions are still property, and it costs money to make, store and deliver copies.

This brings me to why I couldn’t attend the conference to present in person – I had already committed to hosting a Cultural Institution Roundtable in Glasgow discussing how a fee-based system might look designed around property rights rather than intellectual property rights. It’s important to acknowledge concerns in generating revenue and supporting digitization efforts. But they must be balanced against the public’s right to access and reuse of the public domain.

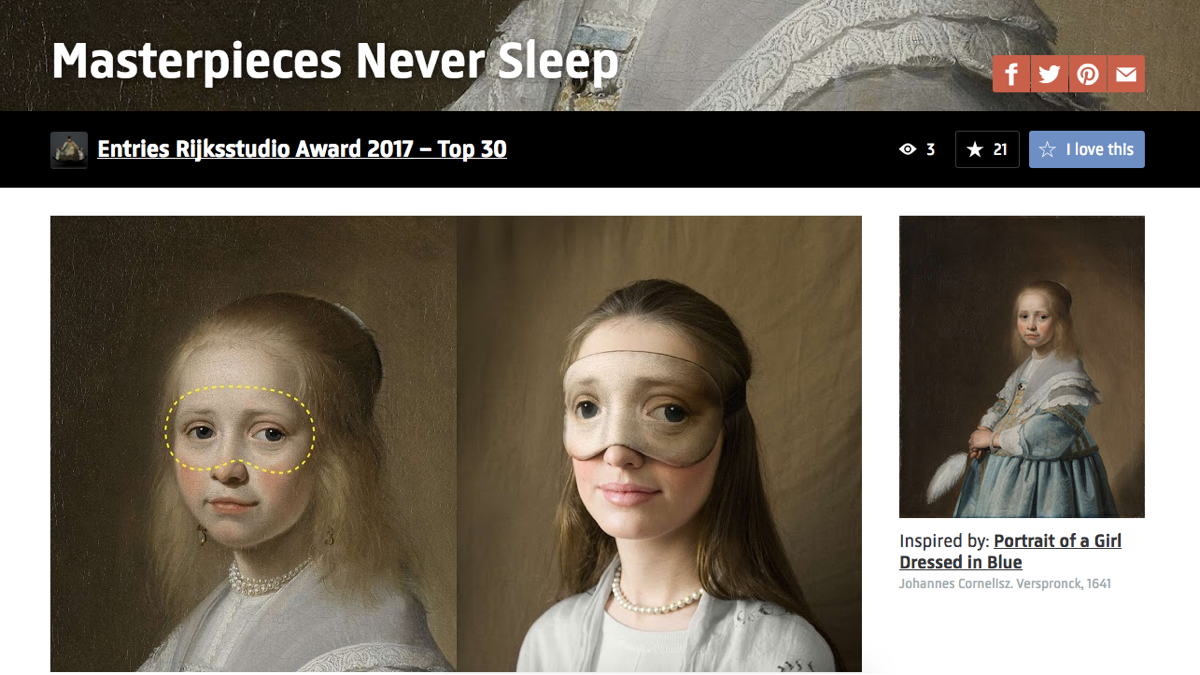

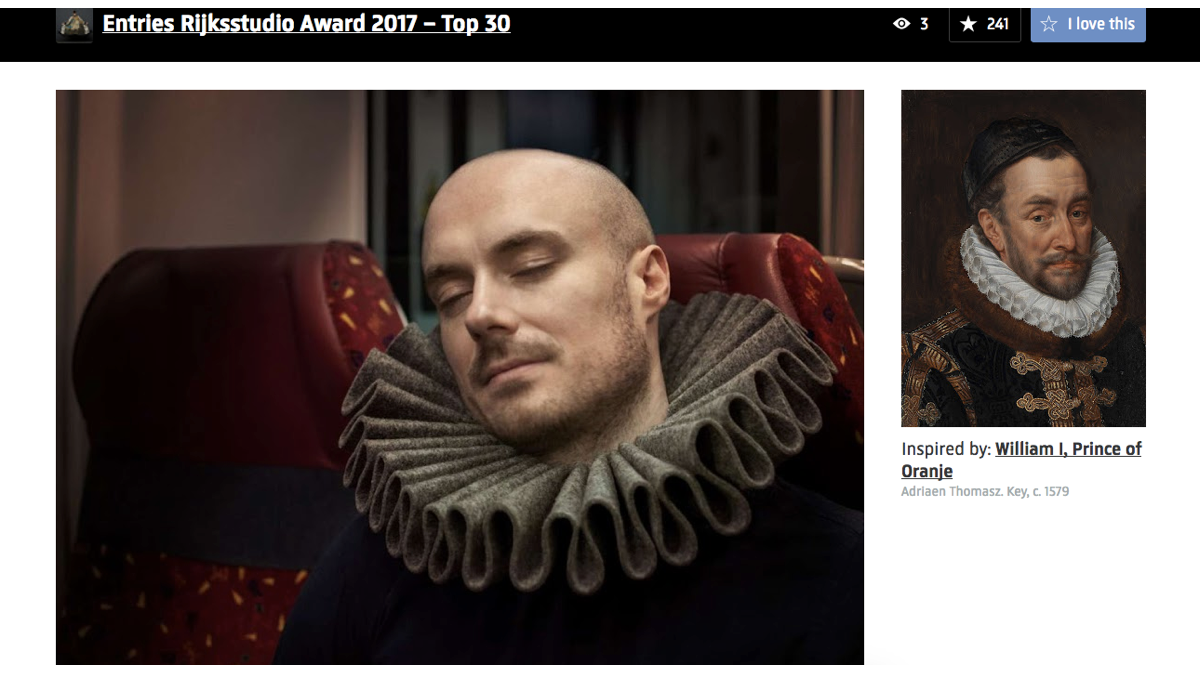

*Enter angel music* – The Rijksmuseum’s Rijkstudio Award

Because this is what the public domain is for.

What you’re looking at is the webpage for the Top 30 finalists for the 2017 Rijksmuseum’s Rijksstudio Award. Of course, the Rijksmuseum has made its entire collection available online for free for all types of use, and the Rijksstudio award is a celebration of that. This year, more than 2600 entries were submitted, which has recently been narrowed down to the Top 10.

Masterpieces never sleep, by Lesha Limonov

User submissions are fantastic, ranging from sleep masks based on paintings in the collection…

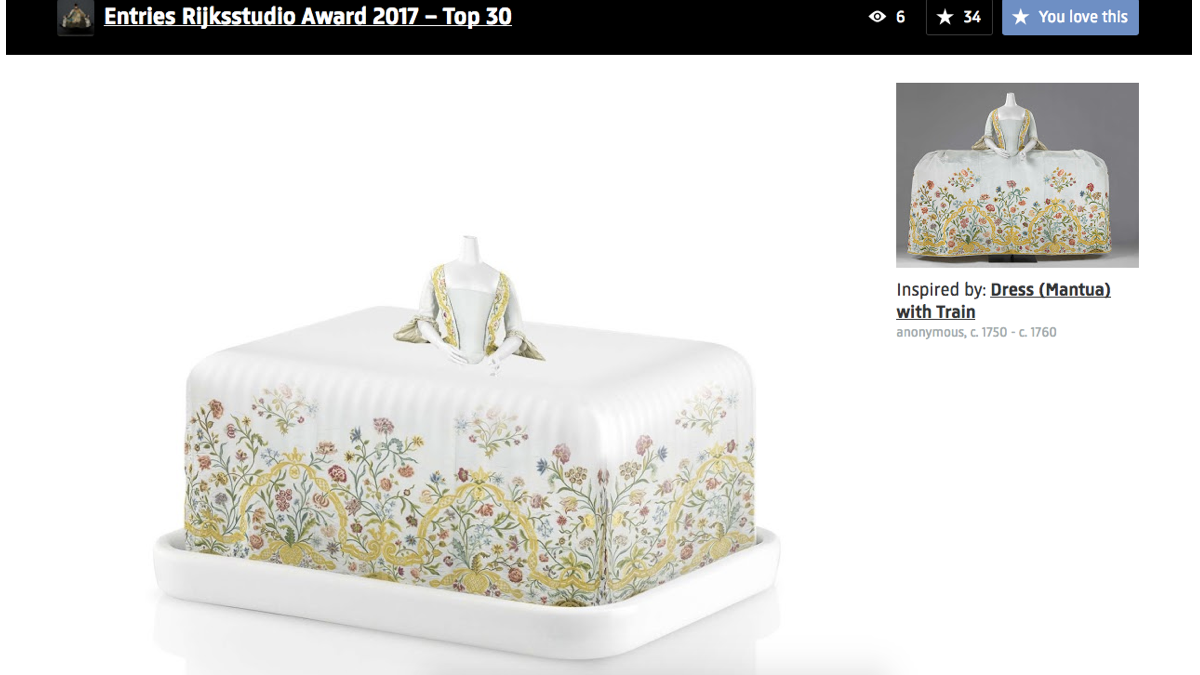

Butter Dish, by Rina Elman

to a butter dish based on a dress… (WE ALL NEED THIS BUTTER DISH.)

Ruffle Neck Pillow, by Paulina Sikorska & Kuba Ludziejewski

to a travel pillow based on one of our favorite Dutch fashions of all time…

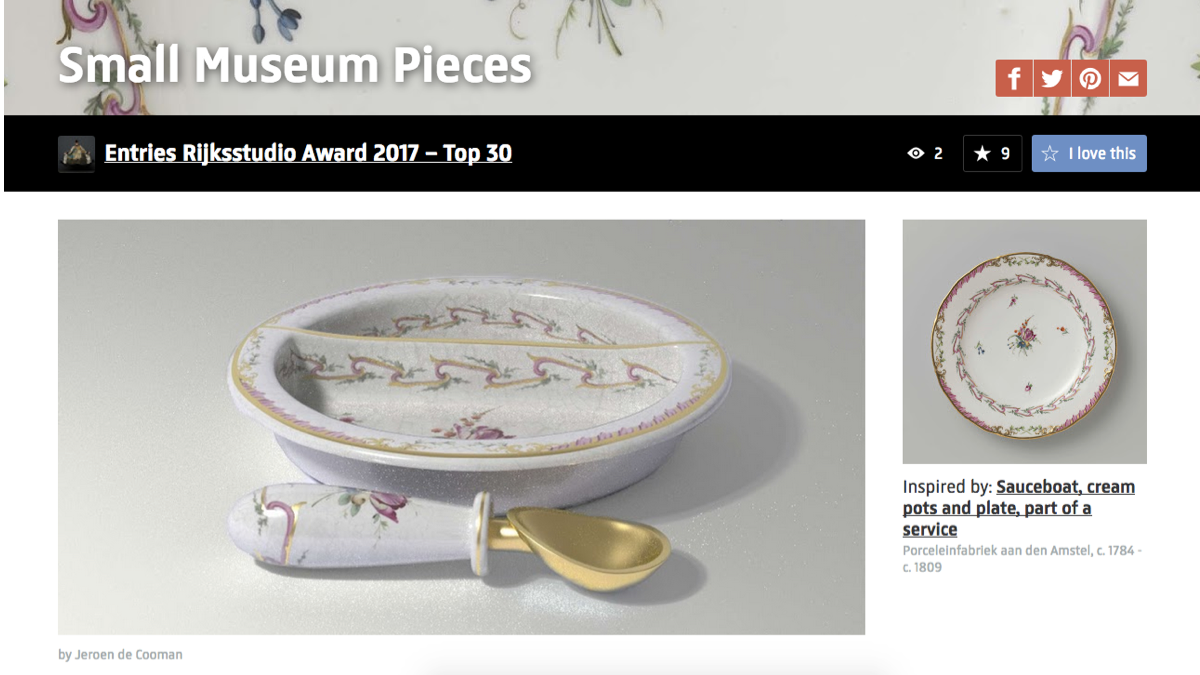

Small Museum Pieces, by Jeroen de Cooman

to adorable baby dishware… (WHO NEEDS A BABY? I WANT THIS FOR MYSELF.)

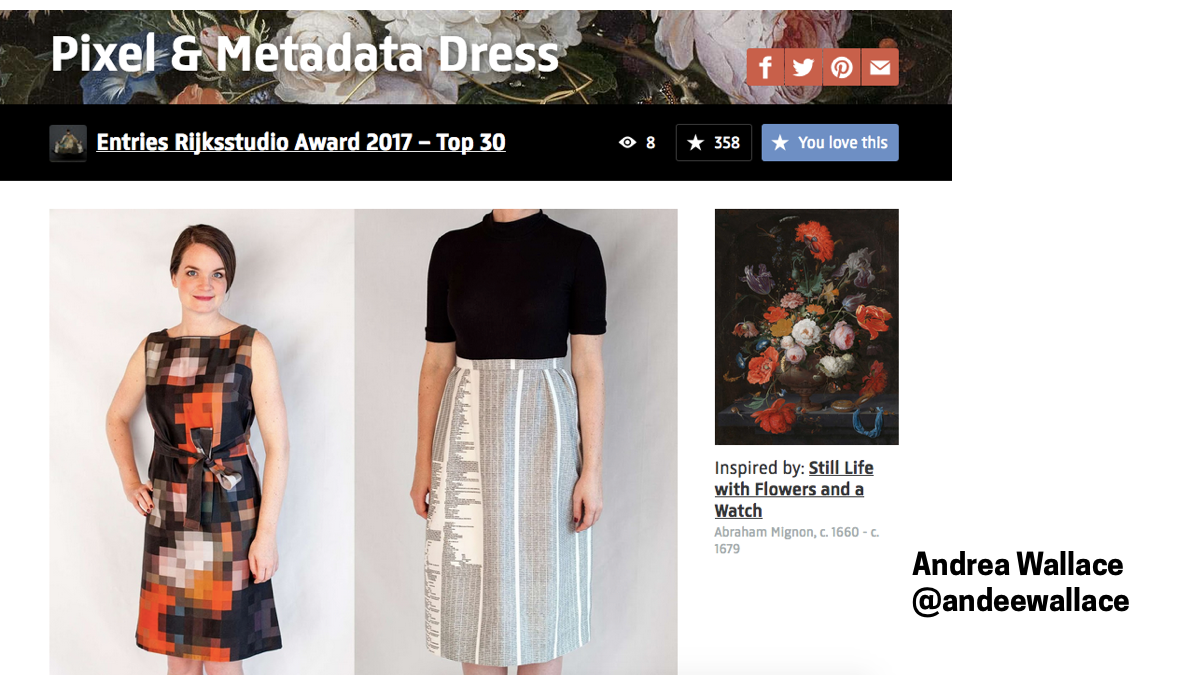

Still Life Pixel and Metadata Dress, by Andrea Wallace

to – OH WAIT – that’s me.

As a shameless plug, this is my entry, which has now made it to the Top 10 (go vote for your favorite)! It’s actually two pieces, the piece on the left is a pixelated version of Abraham Mignon’s painting; on the right is the Rijksmuseum’s metadata which was attached to the image. The concept highlights that visual data and even metadata have a surrogate dimension when it comes to digital reproductions, and it makes transparent layers of authorship in the various components of a digital file.

To conclude, I argue in my research we need to shift our perceptions to thinking of new technologies as not only another medium for making art, but also, and especially, as another medium for slavish copying. And this argument is not new – it’s a debate that goes back to the Renaissance and the first appearance of surrogates, it continues in the debates on justifications of legal protection for engravings and later for photography, and it’s especially relevant today in the context of 3D digitization. And who knows what reproductive technologies are yet to come. But our priority should be to honor public domain works for what they are – works are fair and square in the public domain.