It’s been quite a while since my last post, but I’m back and I blame it all on Display At Your Own Risk (DAYOR).

DAYOR is an research-led exhibition experiment featuring digital surrogates of public domain works produced by cultural heritage institutions of international repute. You can read more about the project here, but it includes both a gallery exhibition as well as an open source exhibition available for download. The preliminary research for DAYOR began back in August of 2015. The project itself is still ongoing; Ronan Deazley (Queens University, Belfast), my project partner, and I have plans to develop it further.

So, what exactly is DAYOR? It’s a lot of things. Let me explain.

First and foremost, it was an experiment to see what would happen if we printed out the images made available on cultural institutions’ websites. What could we learn from the process? How detailed might they be? How pixelated? Would there be any validity to the fear that ‘if something can be seen online people will no longer want to go visit it in person’? We wanted to find out.

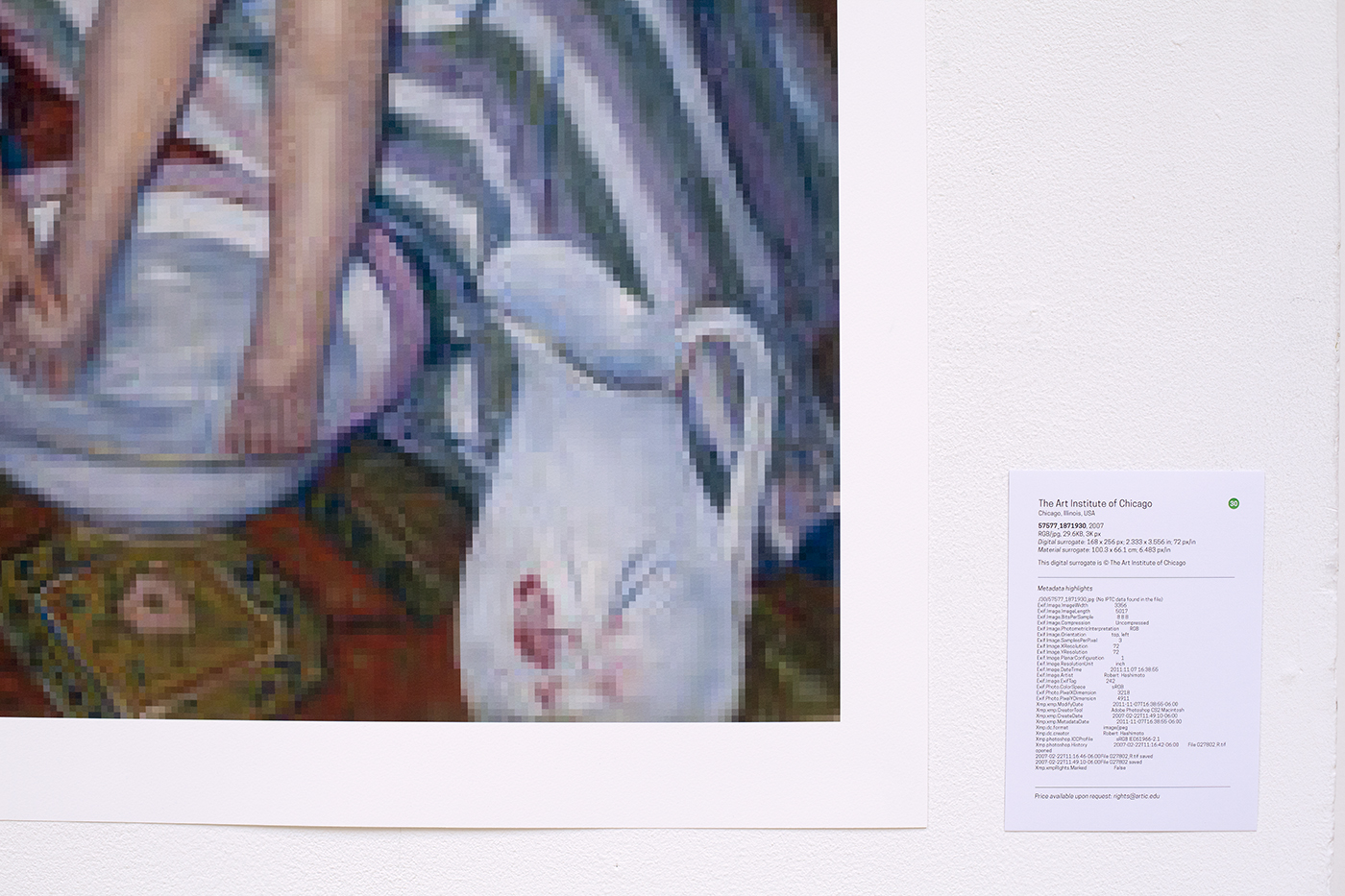

Detail: 57577_1871930, The Art Institute of Chicago, 6.483 px/in, 2016. Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926), The Child’s Bath, 1893, Oil on canvas, 100.3 x 66.1 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. This digital surrogate is © The Art Institute of Chicago.

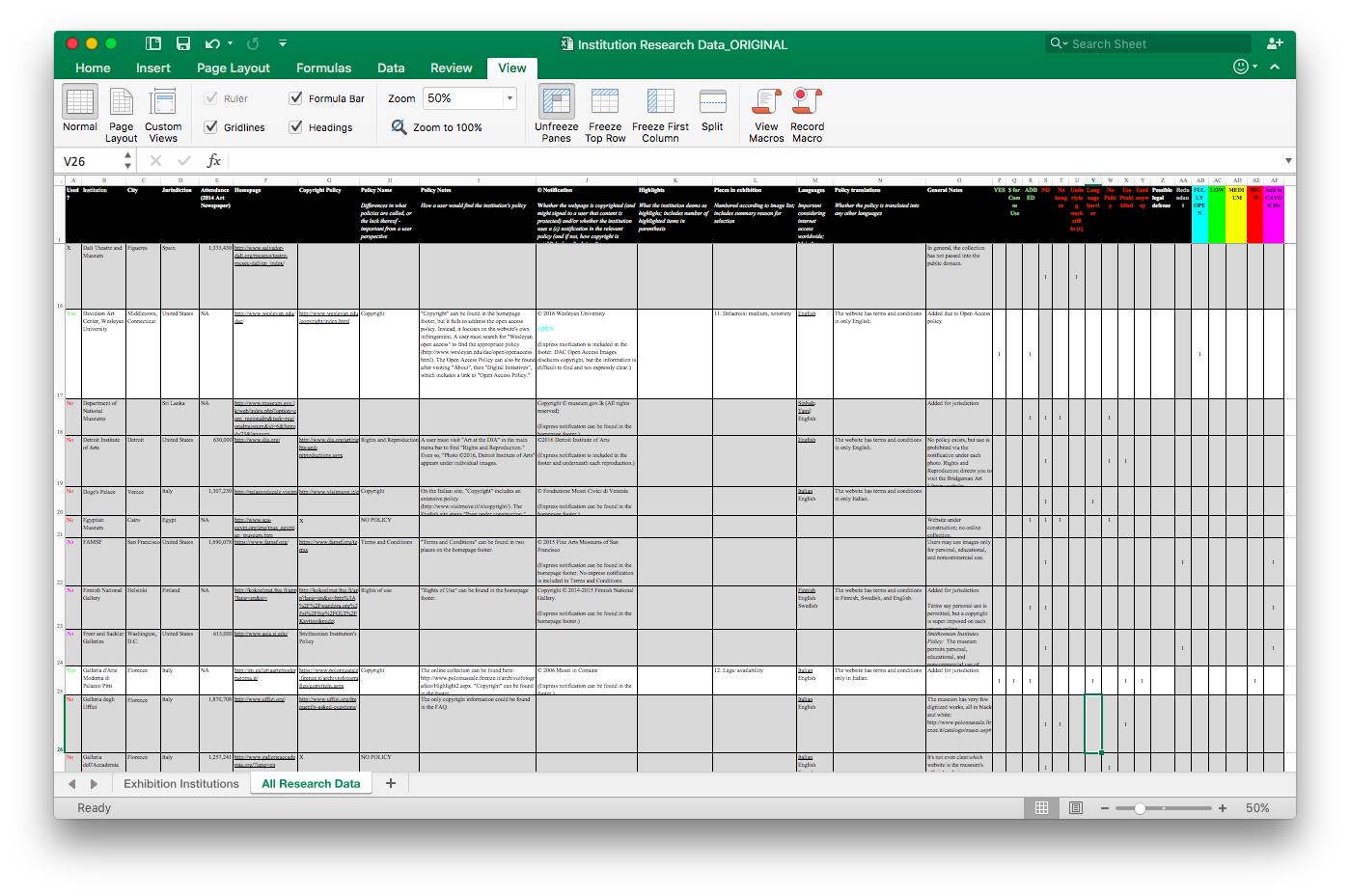

Second, it’s an empirical research project aggregating various claims to copyright over digital collections (and the terms and conditions governing the reuse of) that are put forward by cultural institutions. I performed an analysis of 130 institutions’ websites to see if and how rights were claimed in digital reproductions of public domain works. Of those, 52 institutions from 26 countries made the final sample. We chose 100 digital surrogates in total for the exhibition.

Preliminary research on 130 cultural institutions of international repute, available for download in the open source exhibition file.

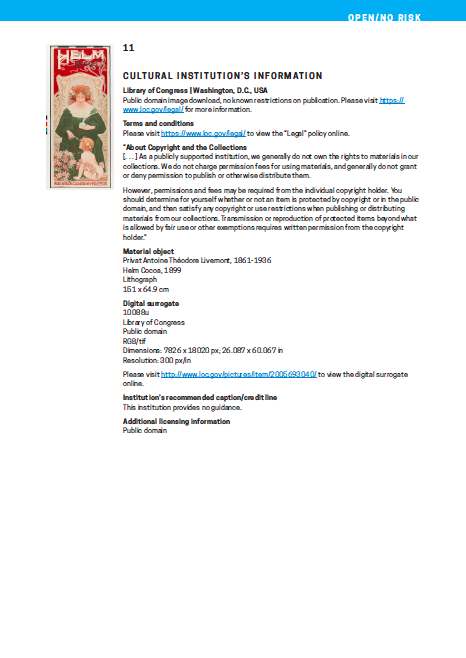

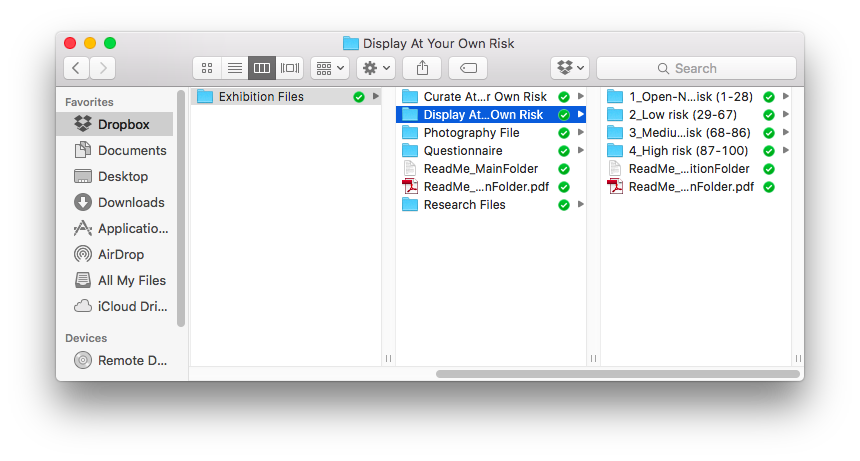

Third, it’s a qualitative research project. I analyzed the terms and conditions of every cultural institution’s website and organized the featured institutions into four risk categories: (1) Open/No Risk; (2) Low Risk; (3) Medium Risk; and (4) High Risk. These categorizations are meant to help the public understand the potential risk in their reuse of online materials and the materials from the exhibition. Each work is accompanied by an information sheet that explains the general and specific restrictions (or not) on public reuse.

The DAYOR exhibition file “ReadMe,” which introduces users to the exhibition file and the risk categorization.

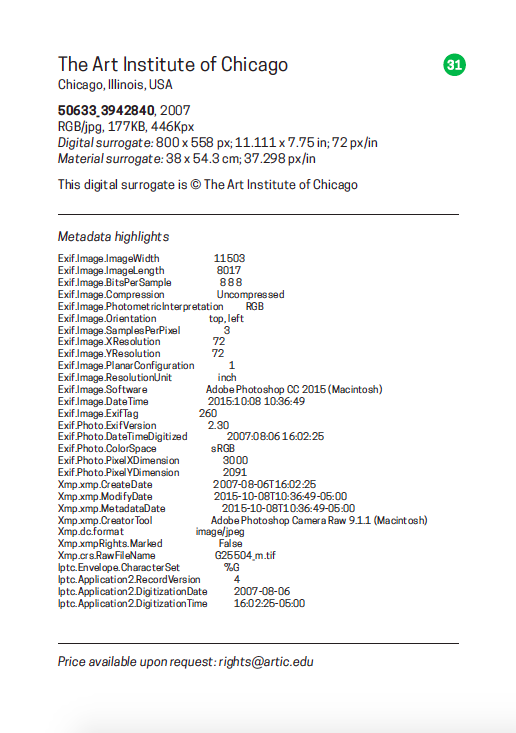

Fourth, it’s a conceptual project in and of itself. We treated the digital surrogates as if they were new original works, meaning they were created by a new author and eligible for a new copyright. The cultural institutions themselves were credited as the author and/or copyright owner. The title of the work was taken from the title of the file. Any text on the title card was taken from the metadata attached to the digital file. Licensing information for purchase of the work was also included where relevant.

Installation detail: 57577_1871930, The Art Institute of Chicago, 6.483 px/in, 2016. Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926), The Child’s Bath, 1893, Oil on canvas, 100.3 x 66.1 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. This digital surrogate is © The Art Institute of Chicago.

Title card for 57577_1871930, The Art Institute of Chicago, 6.483 px/in, 2016.

Fifth, it’s a fully realized exhibition. The online exhibition and the open source exhibition file were made available on April 20, 2016, for World Intellectual Property Day. The file has everything you’d need to host your own version of the exhibition, as well as all of the research data that went into the project. The gallery exhibition opened a few weeks later on June 8. We gave the printed works away at the exhibition’s close.

Display At Your Own Risk website

Detail of exhibition installation at The Lighthouse in Glasgow.

DAYOR’s exhibition opening on June 8, 2016

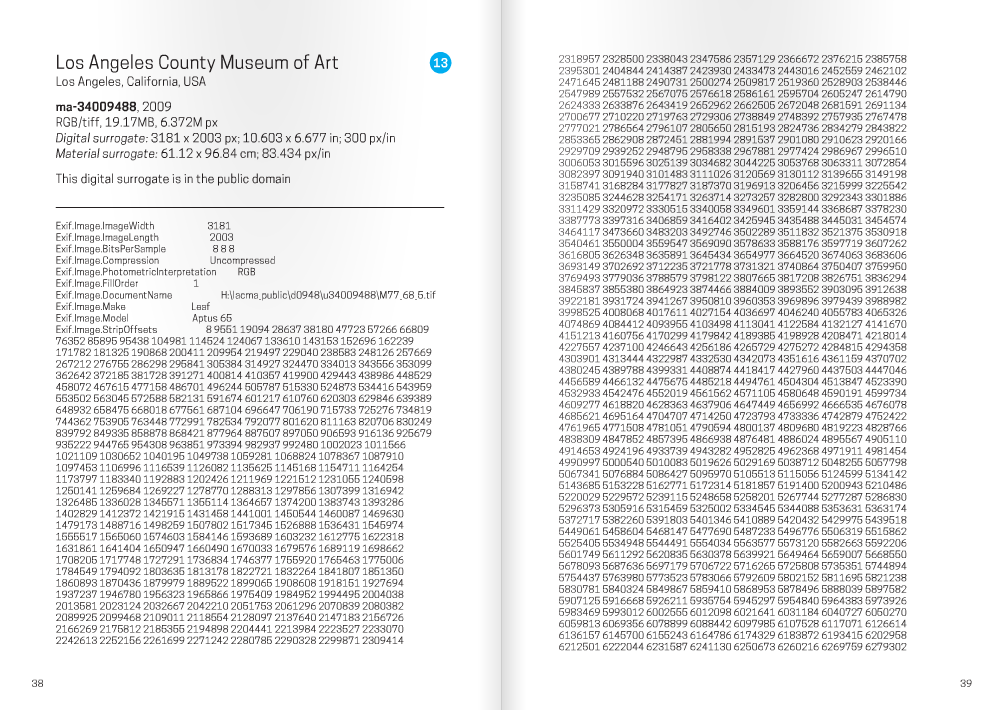

Sixth, it’s a publication. Well, in fact, it’s three publications: (1) a 376-page exhibition companion, featuring a catalogue of the works as well as commentary by academics, lawyers, artists, and museum professionals; (2) a metadata book, featuring all of the metadata extracted from the digital surrogates; and (3) an exhibition poster.

Exhibition catalogue spread for Open/No Risk Work #18 by the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC

The Metadata Book spread for Open/No Risk Work #13 by Los Angeles Country Museum of Art

Seventh, it’s an homage to cultural institutions. We wanted to truly understand and appreciate the difficulties encountered by institutions in digitizing collections and making them available online. What better way to understand than do that ourselves? We curated the works, printed them to scale, digitized them, created metadata for them, created our own policies and made everything available online. In the process, we looked to several institutions for inspiration such as how we formatted the citations and metadata (thanks Yale Center for British Art!), how we organized the information in the file and provided reproduction instructions (thanks Davison Art Center and National Gallery of Art!), and even for the open source font used in all of the materials (thanks Cooper Hewitt!).

ReadMe for Open/No Risk Work #11 by the Library of Congress in Washington DC

It’s also produced by cultural institutions. The works were printed by the National Library of Scotland and the Glasgow Print Studio. They were then digitized by the University of Glasgow Archives Digitization Unit. Throughout the process, discussions with people at these institutions were key to our understandings of digitization challenges faced by cultural institutions.

Finally, DAYOR is an archive in and of itself. Digital cultural heritage is always in flux; with each passing day online policies change, new files are uploaded in place of older ones, metadata becomes more detailed, and so on. What has been released, however, continues to circulate the internet once it’s downloaded and divorced from the institution’s website. DAYOR captures a moment of digital cultural heritage in time and preserves it along with the works’ corresponding rights and reproductions policies.

Open Exhibition File, available for download at displayatyourownrisk.org/downloads

I could keep on going, but I won’t (you’re welcome).

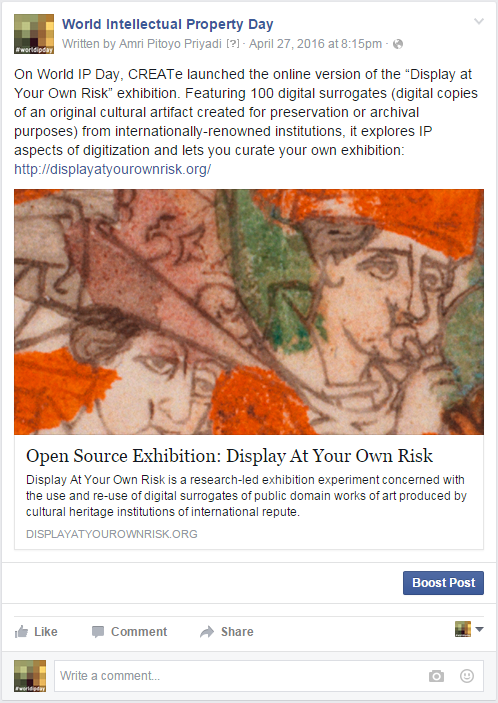

DAYOR consumed my life for almost a year. Since the launch of the website and open source exhibition, we’ve received so much support and we have social media to thank for much of the exposure we’ve received.

Both the World Intellectual Property Organization and Creative Commons promoted the project on more than one occasion (squeeeee!). We’ve received extensive support from the museum sector. The project was also covered by Hyperallergic, a popular Art Blogazine, which really helped to promote its visibility.

*Total fan club screenshot*

*Another total fan club screenshot*

Since the exhibition closed, we’ve been traveling and presenting this first phase our research at various conferences. In fact, we’re hosting a pop-up version of the exhibition at the 2016 Museum Computer Network Conference in New Orleans in November. We’re also tracking the exhibition file downloads and plan to use DAYOR as a springboard for future and related research strands. So stay tuned…

In the meantime, download the file! Get crazy. And by all means let us know what you think.