How to Design a Good IP Policy

What is a “good” IP policy? Well, sorry, but my answer might not be as straightforward as you like. In fact, I’m not here to tell you what your intellectual property policy should say. Each institution has different, unique restrictions and considerations that they must juggle when designing an IP policy. It’s never a one-size-fits-all kind of solution.

However, I am happy to tell you what makes a good policy from a user’s perspective, and this comes from both my experience as a user and my research based on user experience. In most cases, it’s not what you say that makes a good policy, but rather how you say it.

I recently presented on this topic at an orphan works and copyright workshop for the Scottish Council on Archives, along with CREATe researchers Victoria Stobo and Kerry Patterson. I’ll skip the first part of my presentation, which was an introduction to Copy That. Let’s go straight to the meat of the matter: specifically, what you should consider when designing a “good” intellectual property policy.

Here’s what I told everyone at workshop: first, approach the issue with a “Help me, help you” mentality (so basically channel your inner Jerry Maguire). Your goal as an institution is to provide access, right? So, then, how do you design a policy that clearly communicates what can be accessed and how it can be used? Here we go!

♥ Be Accessible ♥

If the public can’t find your policy, then how can they follow it?

Where do you think this information might be when you go to a website? All in one place? In eight different places? Let’s use a couple of examples to illustrate this.

At the National Library of Wales, a user would find at least eight webpages that cover IP issues:

- Conditions of use in the NLW Reading Rooms

- Use of Personal Cameras to create copies in the South Reading Room

- Intellectual Property Rights Policy

- Copyright

- Copyright Information

- Framed Works of Art

- Public Domain Mark

- Notice and Takedown Policy and Procedure

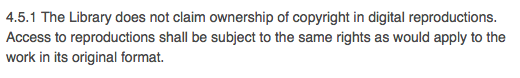

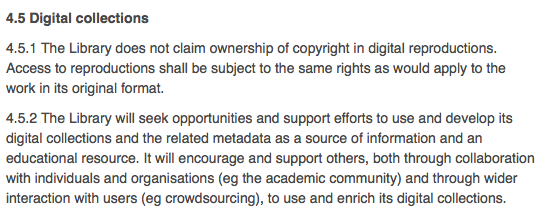

I love using the National Library of Wales as an example, because, as of the time of this writing, they’re the only cultural institution in the UK that has decided not to claim copyright on the digital reproductions of their public domain works. See?

Out of those eight policy statements, where do you think this important provision is? Copyright? Or maybe Copyright Information?

Nope. It’s in the Intellectual Property Rights Policy under “4.5 Digital Collections.”

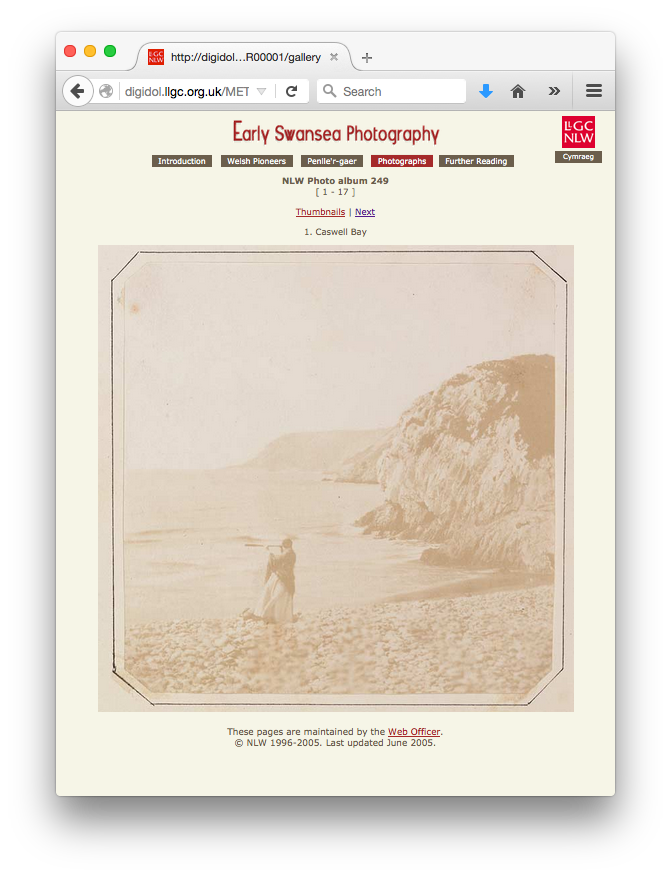

Should a user somehow stumble upon (and understand) this provision, it would seem that a reproduction of anything on the website that’s in the public domain would be fair game for use, right? Well… if you actually navigate through the website you’ll see several instances like this:

Just at the bottom is a copyright claim over the digital image of this photograph from the 1850s. *Sigh* To be fair, websites designed more than a decade ago aren’t exactly ideal interfaces for updating blanket copyright policy changes. In addition, preexisting digitization contracts with third-parties might prevent an institution from releasing these reproductions into the public domain. Still, the Library’s actual policy should probably address this and explain that the policy language trumps such copyright claims, or at least that a third-party contract still controls, right? Otherwise, how’s a user to know?

Just at the bottom is a copyright claim over the digital image of this photograph from the 1850s. *Sigh* To be fair, websites designed more than a decade ago aren’t exactly ideal interfaces for updating blanket copyright policy changes. In addition, preexisting digitization contracts with third-parties might prevent an institution from releasing these reproductions into the public domain. Still, the Library’s actual policy should probably address this and explain that the policy language trumps such copyright claims, or at least that a third-party contract still controls, right? Otherwise, how’s a user to know?

Other websites are similar. The Tate’s policies include:

- Tate gallery rules

- Website terms of use

- Image licensing

- Copyright, permissions and photography

- Copyright ‘orphan works’

- Creative Commons licenses and Tate

- Tate Images Copyright Policy

- Digital Images Reproduction Policy (Tate Images)

- Creative Commons content

When you’re working on your own policy, you should consider whether it’s better to have information in eight locations versus one location, and, if so, why. Think about what you’re naming the policy or its various sub-policies. Is it intuitive? Is it similar to what other institutions are doing? Can a user find the necessary information easily?

♥ Be Clear ♥

Newsflash: legalese is not a universal language (sorry lawyers).

Then again, I’m a lawyer. I understand there are sometimes very specific reasons for why terms must use certain words and say certain things. But the public doesn’t. Nor do they really care. And, sometimes, it’s even hard for lawyers (like me) to figure out what some legalese is really saying, too.

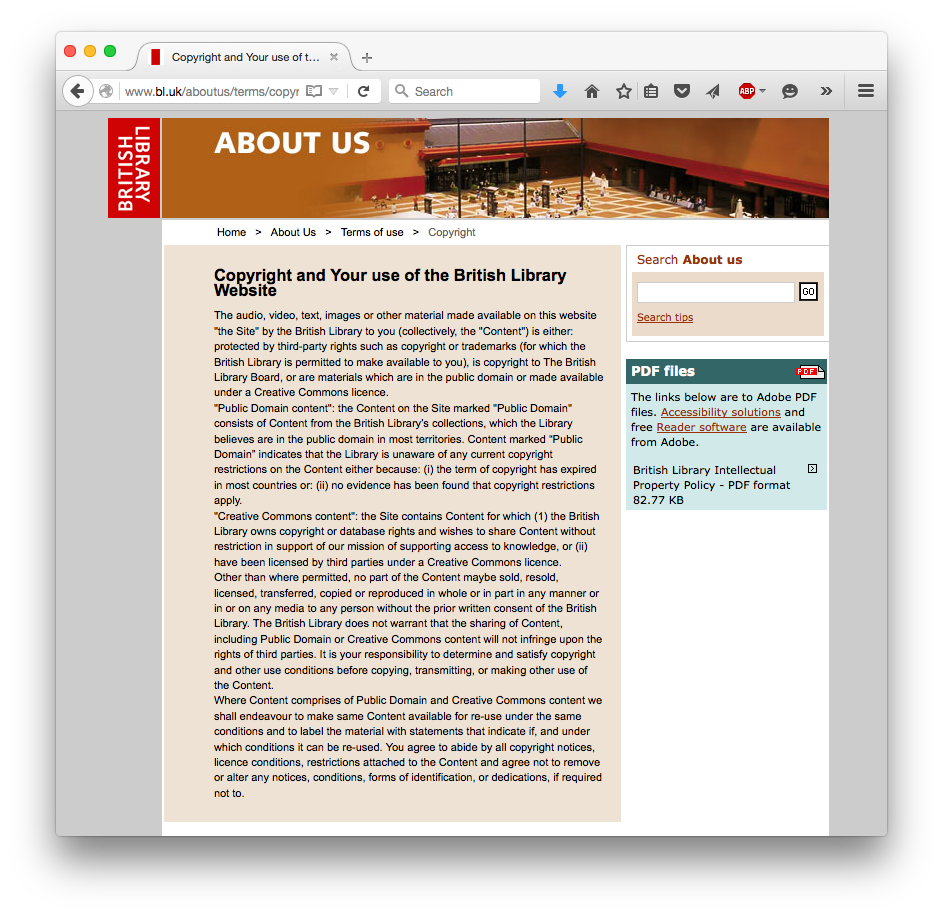

Let’s look at the British Library as an example:

Here’s there relevant portion:

Here’s there relevant portion:

Copyright and Your use of the British Library Websites

The audio, video, text, images or other material made available on this website “the Site” by the British Library to you (collectively, the “Content”) is either: protected by third-party rights such as copyright or trademarks (for which the British Library is permitted to make available to you), is copyright to The British Library Board, or are materials which are in the public domain or made available under a Creative Commons licence.

UM, WHAT? And if that’s not clear enough, there’s an eight page “British Library Intellectual Property Policy” to help.

Often, you must use certain language to insulate yourself for legal reasons. That’s usually what the legal teams behind cultural institutions’ policies are doing. But don’t just insulate, educate! Use legal language when necessary, but explain to the public what it means. Be consistent with the language that you use.

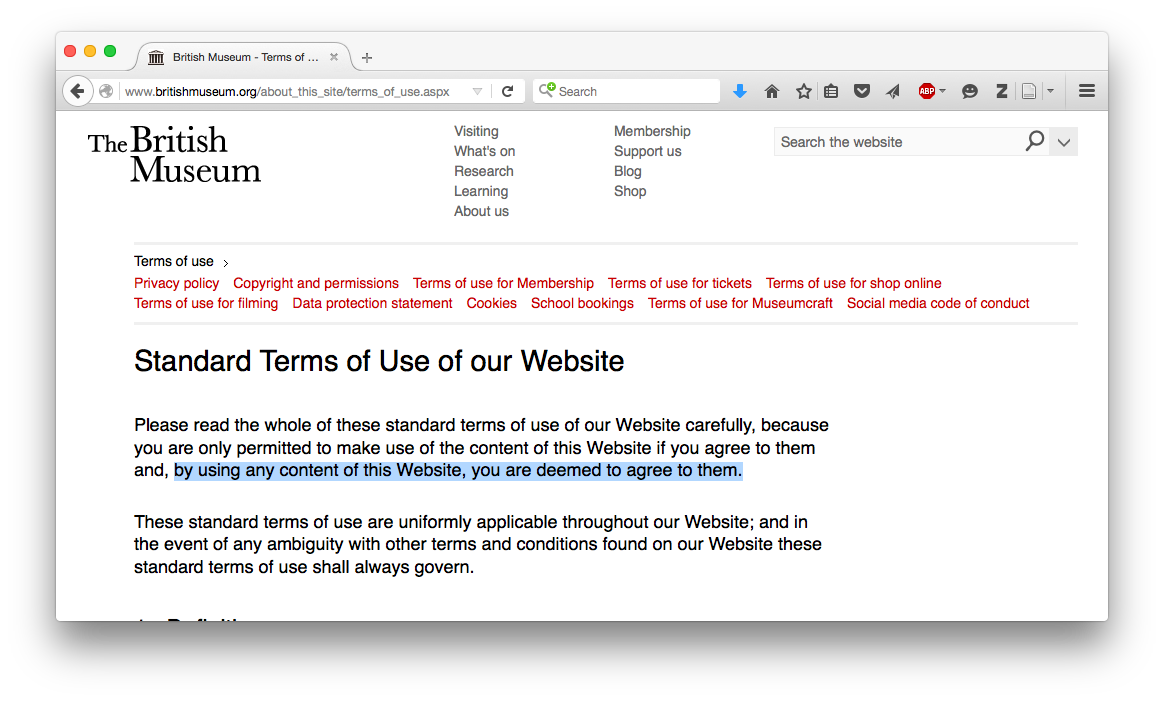

Finally, if you claim copyright, don’t hide the copyright carrot. Say it outright. Like this:

♥ Be Straightforward ♥

Users really just don’t know. Terms and conditions, schmerms and conditions. What does it all mean?

If you want people to respect your policies, tell them that. Tell them how they can do that while encouraging access and reuse. Tell them why respect is important, such as to preserve the object’s educational context, the author’s (or the institution’s) intellectual property rights, and so on. Public education should be your friend.

Instead of being general, i.e., “by using any content of this Website, you are deemed to agree to [the Standard Terms of Use]”:

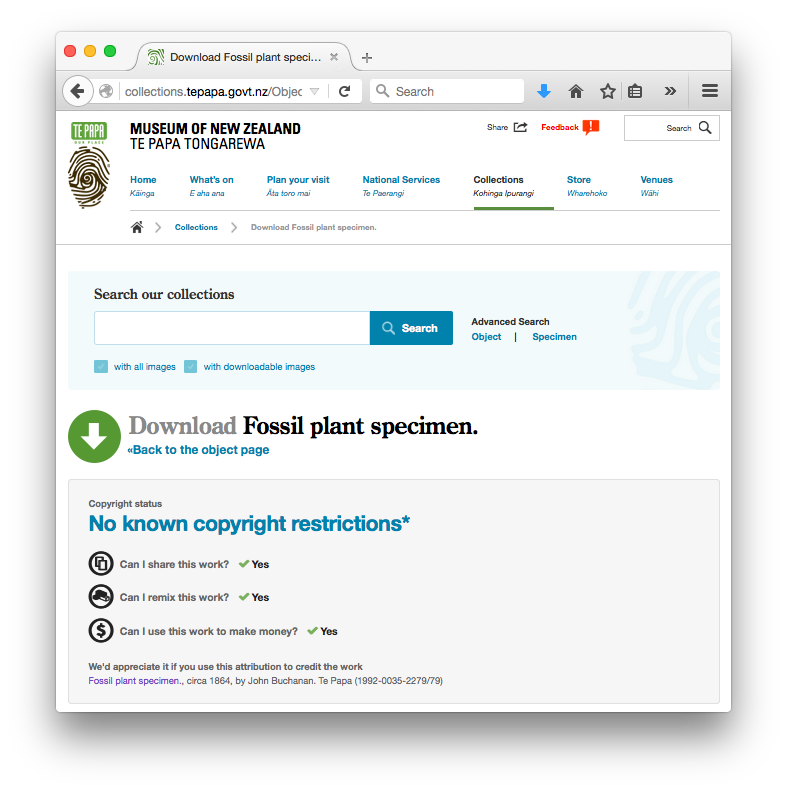

Be specific:

Tell users how they can use the image and how they should attribute the work (see that above?).

Tell users how they can use the image and how they should attribute the work (see that above?).

Europeana and The Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (based on Europeana’s guidelines) both have excellent guidelines for ethical use.

♥ Be Realistic ♥

People are going to use your content whether you like it or not. Sorry, but it’s true.

How so, you say?

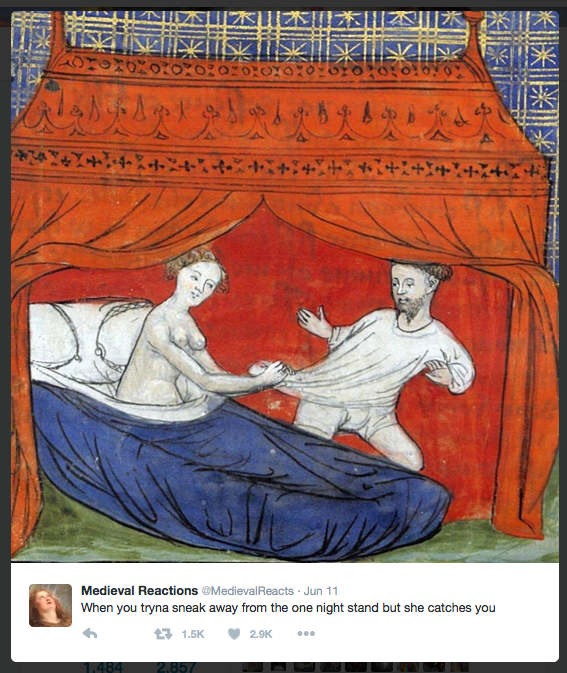

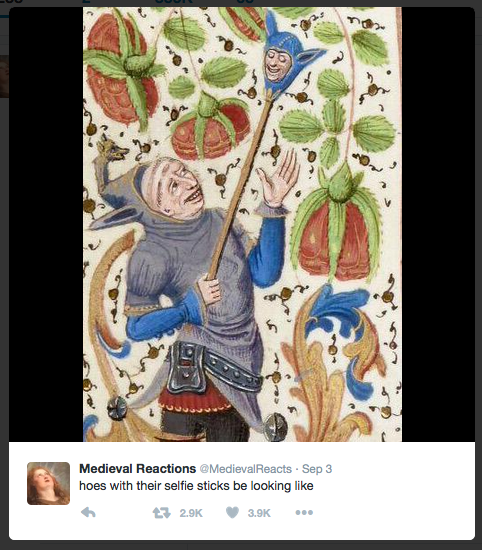

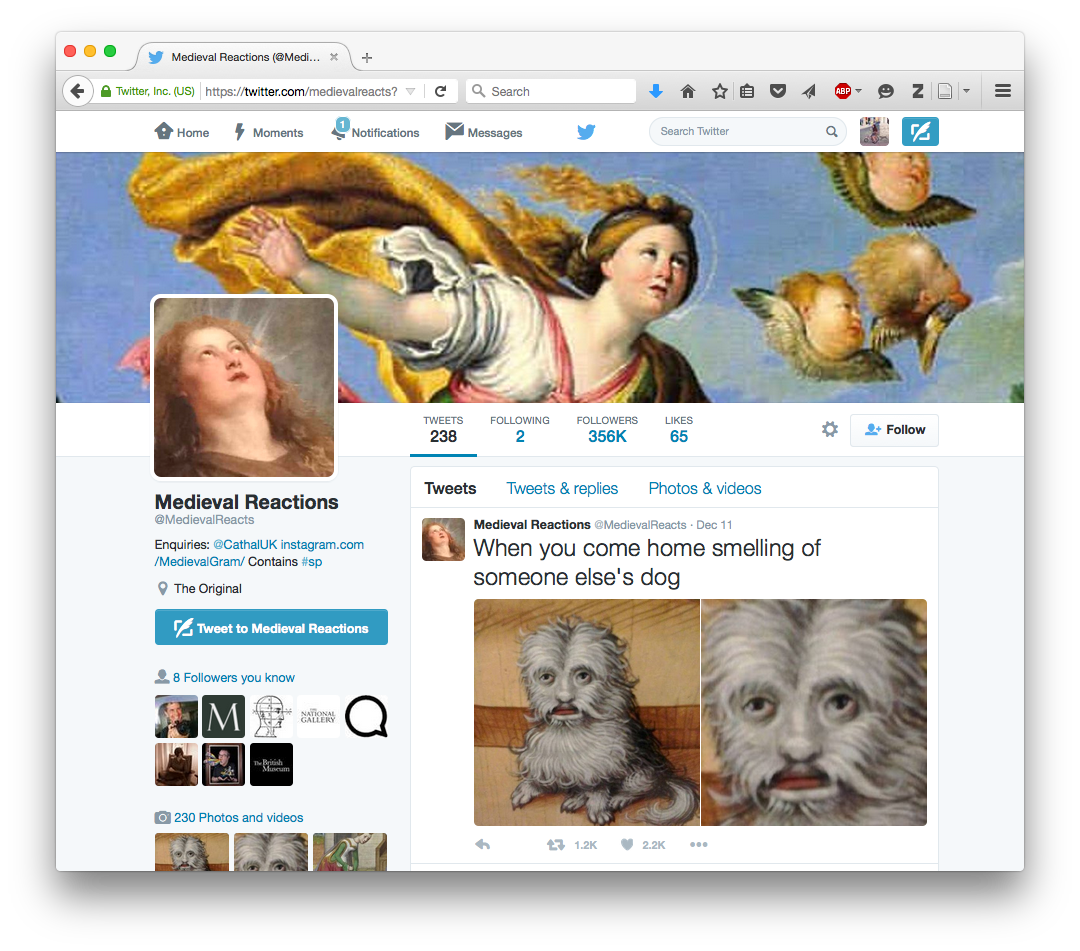

Here’s an example of a Twitter account that uses images from cultural institutions and the Internet, for commercial purposes, and has more than 350,000 followers:

Why do people love it so much? You decide:

Why do people love it so much? You decide:

I’ve written on this issue before too, specifically on the Ugly Renaissance Babies Tumblr.

Most institutions have policies that are pretty hard to enforce. After all, how do stop people from using your images on the Internet? Well, you kind of can’t. But you can educate people how to use them respectfully, as previously mentioned.

Finally, if you decide to have an enforcement provision in your policy, great. But design an enforcement provision you actually respect and enforce internally, too. Otherwise, what’s the point?!

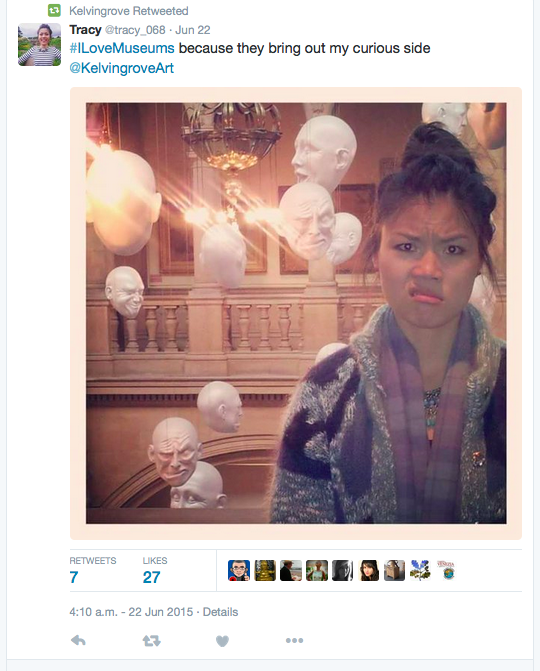

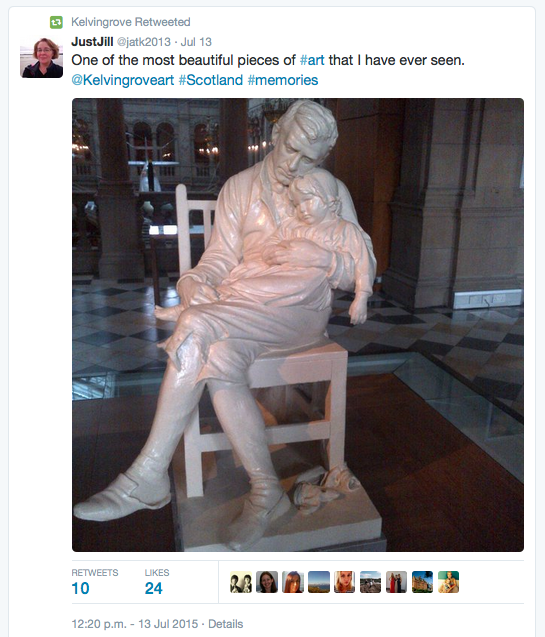

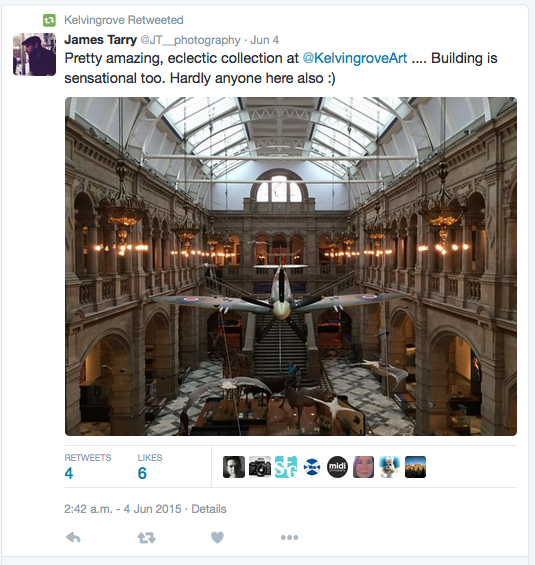

Glasgow Life has a policy for all of the Glasgow museums and libraries that requires visitors to go to the information desk and get formal permission in order to take photos (or even sketch) in their galleries:

A form to request permission to draw, photograph and make video recordings in Glasgow Museums stores and galleries for personal use is available from all our museums and must be completed before undertaking any of the above.

So… do you think that all of these people filled out permission forms?

Note: these are all retweets from the Kelvingrove’s Twitter account.

And my personal favorite, which is a Kelvingrove retweet from a commercial photographer’s twitter account (aka commercial use!):

You can find dozens more on the Kelvingrove’s Twitter page. Think about your policy and how it is (or isn’t) being enforced by your own staff and administration.

♥ Be Reasonable ♥

If you want people to pay a fee for your images, ask for a reasonable price.

Ideally? Charge a standard, flat fee.

Most institutions distinguish between noncommercial (like for personal research or educational purposes) and commercial use. This practice doesn’t necessarily present a problem, especially when a license for noncommercial use is provided at a standard, flat fee.

Both the National Library of Scotland and the National Library of Wales do this for requests made through their image services. For example, the National Library of Scotland charges £7.50 for a high resolution JPEG digital download of an existing digital image. The National Library of Wales charges £3.50 for low resolution files and £14.00 for high resolution files. Both institutions permit (to an extent) free direct downloads of images on their websites.

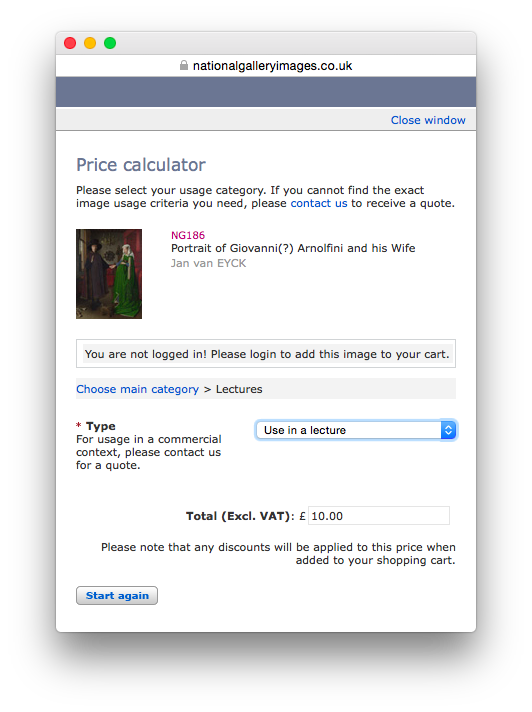

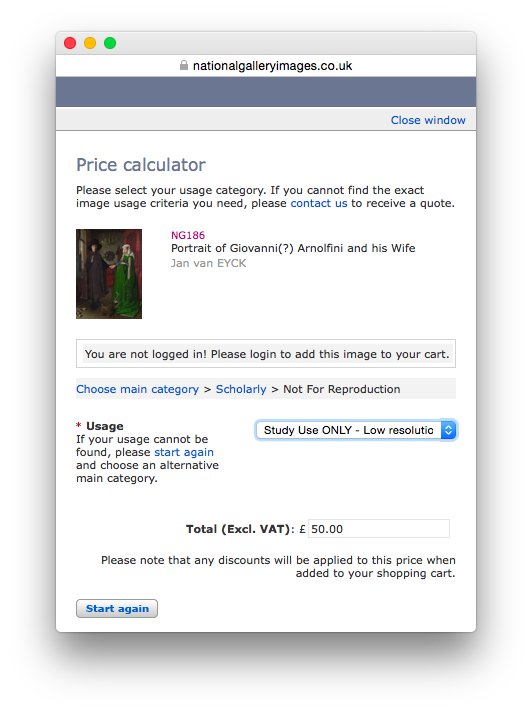

Compare this to the pricing and supply structure used by the National Gallery, which provides a price calculator for requests made through the National Gallery Picture Library.

For scholarly use (low res and for study only) of this van Eyck painting, the Gallery charges £50.00:

Compare this to £10.00 charge for a noncommercial lecture:

Compare this to £10.00 charge for a noncommercial lecture:

What’s the difference? Both are noncommercial, educational uses. Further, if I wanted to use this image for both a lecture and personal study, I am technically required to pay for both licenses: £60.00 in total. What’s to stop someone from downloading something for a lecture AND studying it? Or printing it? From a user’s perspective, what, really, is the difference?

To be fair, the National Gallery offers a scholarly waiver for “free access to high quality images for scholarly publications including academic books and journals, student theses and academic presentations or lectures” for requests made to the National Gallery Picture Library. In addition, you can download decent images of some public domain works, like the van Eyck, directly from the National Gallery main website for noncommercial use under a Creative Commons license. The Gallery’s examples of noncommercial use include “Research, private study or for internal circulation within an educational organization (such as a school, college or university)” and “Non-profit publications, personal websites, blogs, and social media.”

Even so, why all the different ways to pay or get for free practically the same thing? Why not just provide medium or high resolution images to users without all the options and barriers? How’s a user who goes to the National Gallery Picture Library website supposed to know that he could have gotten the same image for free through the National Gallery main website?

♥ Be Helpful ♥

First, help your audience use your images the way you want them to by providing citation examples directly next to the image where possible. This makes it easier for users to protect a work’s context.

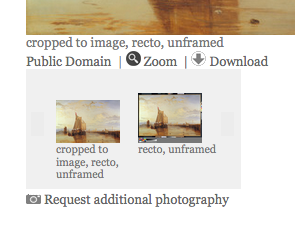

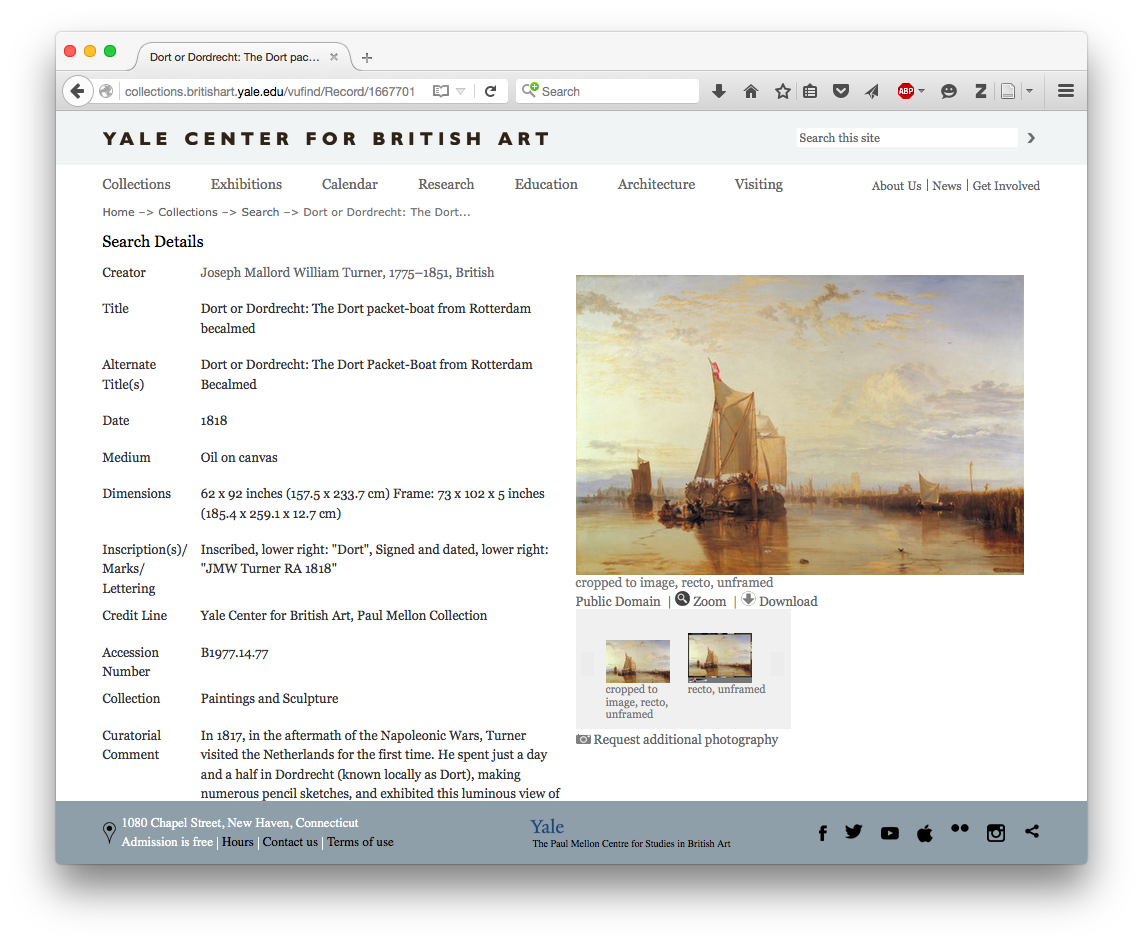

The Yale Center for British Art permits downloads at medium and high resolution and provides a citation for each work. For example, take this Turner painting:

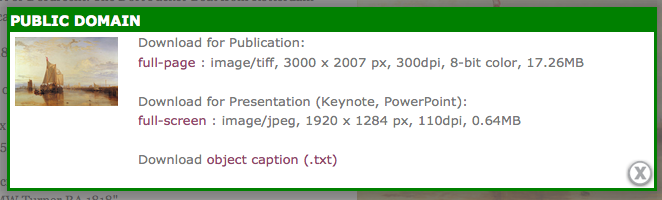

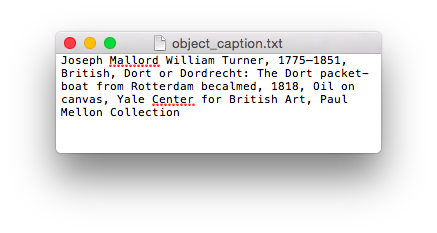

Just below the image is a “Public Domain” note, with two different versions for download: one cropped to the image and one with a black background and color strip (an industry digitization standard).

Just below the image is a “Public Domain” note, with two different versions for download: one cropped to the image and one with a black background and color strip (an industry digitization standard).

Here’s a close up:

Click on your preferred version and this pops up:

Which resolution would you like!? So exciting! Also, see that “Download object caption (.txt)” link? This is what you get:

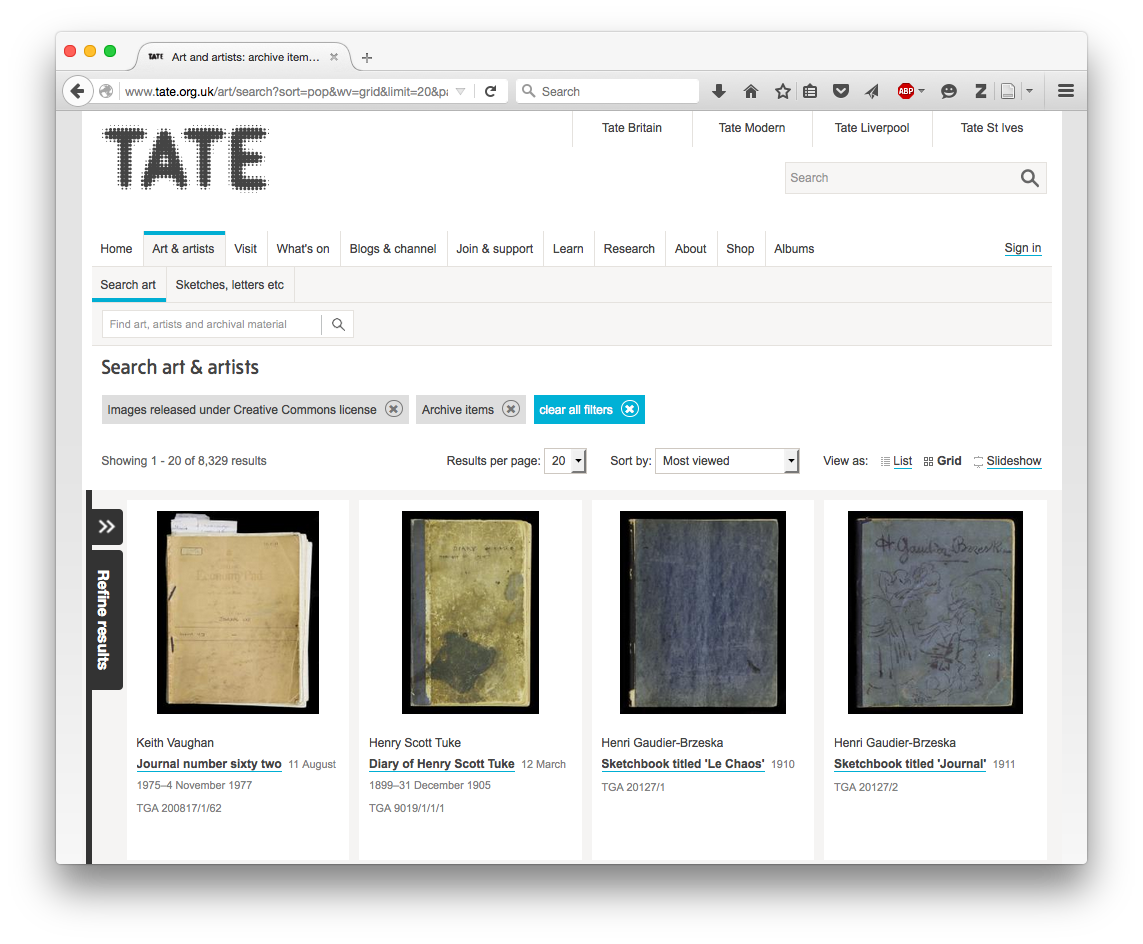

Second, make it easy for users to find the content that you make available online for free. Some institutions do this by enabling you to search via copyright status. For example, the Tate allows you to filter its collection via Creative Commons license.

Finally, tell users where you’ve contributed content for unrestricted use on other sites, like Flickr, Wikimedia Commons and Europeana. It’s great that you’ve done this… brag about it!

♥ Be Generous ♥

(… you know, as much as is realistically possible.)

First, sound generous. Draft information in a positive way. It shouldn’t be about what you can’t do, but instead about what you can do. Access is the ultimate goal anyway. Draft your language in a way that focuses on access, not restrictions.

Second, (ideally) don’t claim a copyright over reproductions of public domain works. Instead, and if you have to, use your terms and conditions to limit use to personal, educational, and noncommercial purposes. This is what the Smithsonian Institutes has done.

Third, provide decent resolutions. Please?

Finally, for jurisdictions that recognize fair use and fair dealing, think of it as your friend instead of your enemy. Audiences in those jurisdictions are going to be able to use your works as permitted by the law, regardless of how restrictive your terms and conditions are. Why not use fair use/fair dealing as a minimum standard for permitted use? Start there when designing your policy. At the very least, you should mention it in your policy.

♥ ♥ ♥

Ultimately, think about your audience and who they are. Why are people on your website looking to use your work? For educational purposes? Let them. Tell them how to protect the educational context of the work. Why are people taking photos in your galleries? They’re interested in the work. They also want to take selfies and post their photos on social media. So tell them whether or not they can! You’d be surprised how many institutions have no social media policy for this type of use.

So many people I’ve spoken to are behind the scenes at cultural institutions advocating for opening up their collections. Not only does it take time, but it also requires a consensus about what “open” means to an institution. In the meantime, focus on opening up your policy in a way that enables the public to use the works you’ve already made available.

(Finally, if you’re working on making these changes in your policy and want to tell me all about it, please reach out! Use the contact form at the bottom of the About page ♥!)