This post is part one of two posts related to my dad’s stint in photographing Memphis wrestlers during the 1970s.

What do my dad, orphan works, and 1970s Memphis wrestling have in common? Surprisingly, a lot. And it all started with a camera.

Before I get to it, let’s talk shop for a minute.

What is an Orphan Work?

An orphan work is a copyright protected work – like a book, a painting, or a photograph – for which the work’s author cannot be identified or located. We call this work an orphan work because we don’t know who to go to for permission to use the work.

Some types of orphan works can be more problematic than others. Take a painting, for example. A painting exists as a single, unique object. If that painting is in a museum, the museum will protect the original author’s rights. In theory, no one will be able to copy or make money off of the painting other than that original author.

But what about other types of orphan works? And especially works that exist in multiples?

Let’s say you have a photograph from the 1970s, but you don’t know who took it. Maybe you picked it up at a yard sale or maybe you found it in a stack of photos in a box somewhere. That photograph is an orphan work: the work is still in copyright, and someone enjoys that copyright, but you don’t know who or where that someone is. That photograph might be the only photograph of its kind out there. But what if it’s not? What if there are hundreds of copies of photos out there? And what if some of those photos are uploaded to the Internet?

This is where my dad comes in.

My Dad the Photographer

Background: It started in 1972, when my dad, Robert (Bob) Wallace, bought a photography studio while living in Crawfordsville, Arkansas. He and his business partner, Louise Lawman, ran the studio for a couple of years before they closed it down.

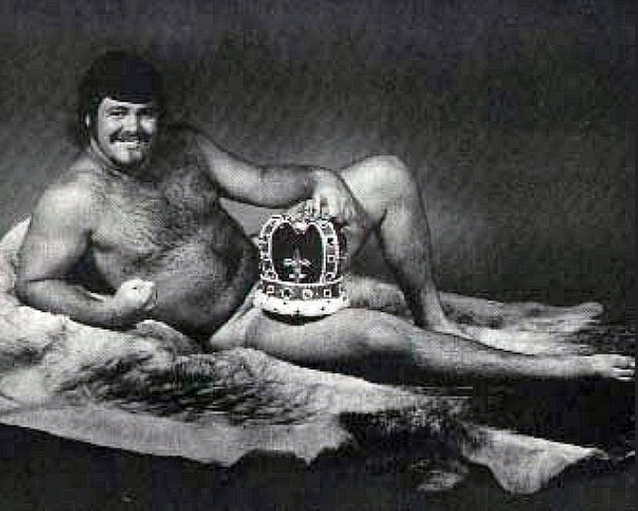

While it was open, my dad, Louise, and a man who worked in a print shop named Jim Blake started a wrestling magazine. Blake was a close friend of the wrestler Jerry Lawler; the magazine was Blake’s idea. Jerry Lawler was known as “the King” in Memphis… along with Elvis, of course. They all got the wrestlers on board and had them sign consent forms to take photographs during events.

According to my dad, it was a lot of work:

“We took pictures on a Monday night—it was Monday night wrestling at the Coliseum in Memphis. We would go out there and take pictures, and we’d get out of there about 11 or 12 [at night]. We’d go straight back to the studio, and a group of us—about 4 or 5—we would develop the film, make a contact sheet, and the guy that was kind of like our publisher […] would go through and make a check on each [photo] that he wanted printed. And the while we were printing 8x10s, he would be writing the dialogue. So when the sun came up Tuesday morning, we were at the printers getting the silkscreen [plates] and having those made. Then Tuesday afternoon we’d take them over to the printer, and sometime Wednesday we’d pick up maybe a thousand magazines. They weren’t slick cover, they were just regular paper, but they were folded and saddle stamped and came with a cover that said something like ‘Wrestle Mania’. This [wrestling] circuit was out of Nashville, and they had other wrestling sites like Jonesboro, Memphis, Chattanooga, and some other towns. We would follow those wrestlers for the rest of the week until [the next] Monday night. And we would go to those wrestling events and walk around selling these magazines for a dollar-a-piece. It went pretty good, but we didn’t make that much money.”

Later, they had a chance to go to Nashville and talk to the guys who ran the wrestling circuit. They waited in the office all day before the secretary came out and told them the owners had decided against meeting with them. Apparently, the owners didn’t see an opportunity to make much money from the magazine. Not only did they turn my dad and his partners away, but they also forbid them from taking photos of events in their venues in the future.

This basically did my dad’s studio in. He and his partners were deeply invested in the project, and the loss meant the studio’s efforts had “gone to pot.” So they “just locked the door, loaded all the equipment out, and shut the whole thing down.”

Fast forward to about a year ago: My partner, Michael, and I were paying my dad a visit. Michael and my dad started talking about photography. I had known about my dad’s photography studio, but only that it had been open for a couple of years, because it had been so hard to support.

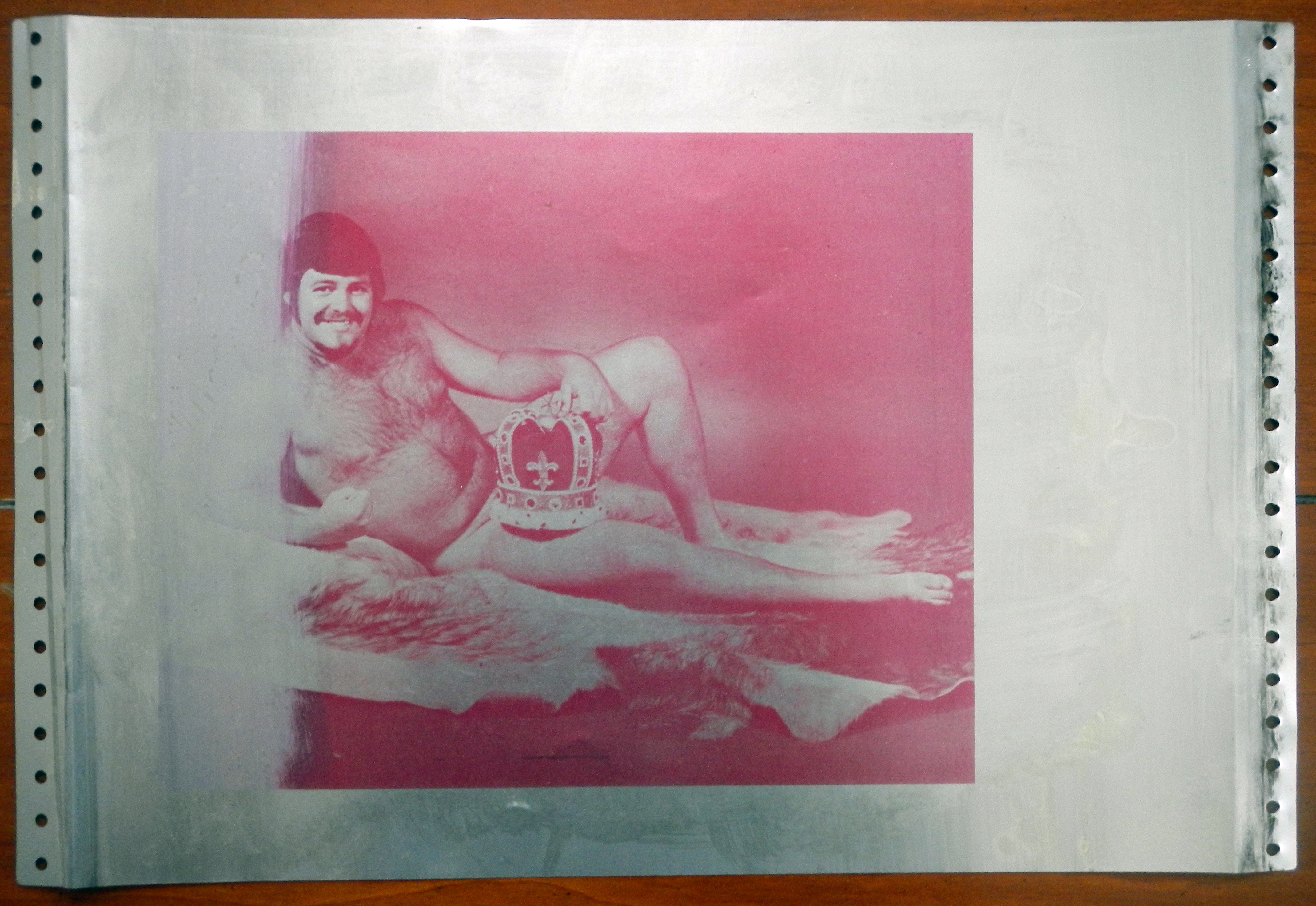

Michael and my dad disappeared upstairs to look at my dad’s old equipment. A bit later, Michael came down with this fantastic beauty:

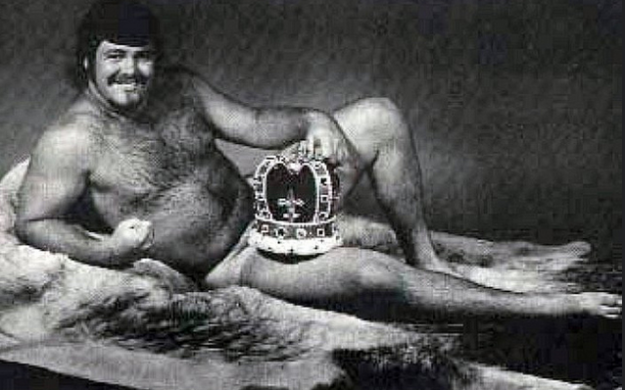

This is one of those silkscreen plates my dad was talking about. It’s print of a photo that my dad took of the Memphis wrestler Jerry “The King” Lawler.

Michael and I, for obvious reasons, found the plate amazing. Unfortunately, though, my dad no longer has a print of the photo. Michael went online to see if he could find a copy—and he did:

This is where orphan works come in.

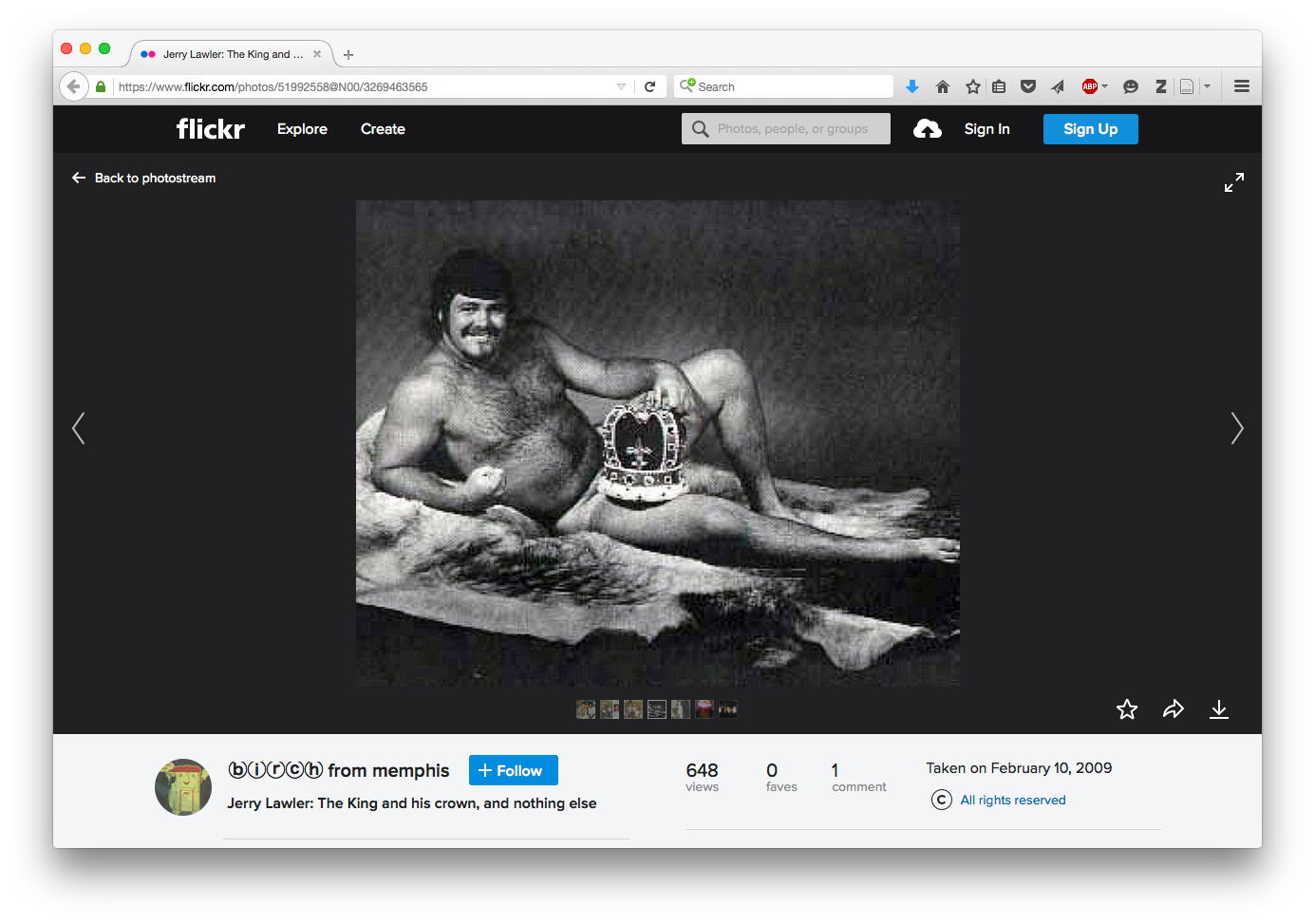

The photo was actually uploaded by someone on Flickr, under the account name of “Birch from Memphis.” Birch doesn’t list my dad as the author, nor does he credit my dad’s studio anywhere on the page.

Birch titles this photo, “Jerry Lawler: The King and his crown, and nothing else.” It’s included in Birch’s album “Memphis Wrestling.” According to Birch, this photo was “Taken on February 10, 2009” and is copyrighted as All Rights Reserved.

According to Yahoo’s terms, which owns Flickr, All Rights Reserved means:

“You, the copyright holder, reserve all rights provided by copyright law, such as the right to make copies, distribute your work, perform your work, license, or otherwise exploit your work; no rights are waived under this license.”

This means Birch is claiming that the photo is his own work for which he holds the copyright. But… my dad took the photo.

With all this in mind, I decided to ask my dad exactly what he knows about his copyright.

Bob Wallace and Copyright

My dad knew he had a copyright. He was unsure how long it lasted or what it got him. In fact, he was a bit shocked when I told him his copyright lasted until his death, then passed on to his heirs (my sister and me) for the next 70 years. He was also unfamiliar with the term “orphan work.”

I explained to my dad that because this photo was out there all over the Internet, with no one attributing it to him, it qualified as an orphan work. He and I both know he is the copyright holder. But these people circulating the copy don’t know who he is—nor do they probably know they’re infringing someone’s copyright in the first place.

Here’s a bit of our conversation:

Me: “Knowing that your photo is floating around out there… do you care?”

Bob: “It kind of bothers me if someone is making money off of it.”

Me: “What if someone isn’t making money off of it?”

Bob: “Well, if he’s going to put it out as his and receive credit for it, then that would aggravate me because it’s not his photograph. It’s mine.”

Me: “Do you think I should send an email to Birch?”

Bob: “I’d be interested in notifying Birch that he is displaying a piece of work that I have the copyright to, and that he should consider that he’s using someone else’s work and that person is aware he’s put it up on Flickr.”

Me: “If he added your name to it, would you feel like the issue has been resolved?”

Bob: “I would appreciate it if he would add my name to it, but I would also appreciate that if someone wants to use it, I would expect him to share any compensation he receives with me.”

Me: “He wouldn’t be entitled to receive compensation, because it isn’t his work.”

Bob: “Well, entitled and doing are two different things.”

That’s certainly the truth. In fact, that’s one of the main issues photographers experience when trying to commercialize their works through the Internet.

Finally, I asked about how someone was supposed to get in touch with him:

Me: “So, how does Birch know it’s your photograph?”

Bob: “Well… he doesn’t.”

And there you have it. It can be incredibly hard to track down an author to get permission (but it doesn’t mean you should go ahead and use a work if you can’t locate the author). After all, this photo is one of many copies that have been floating around since the 1970s. And what do we really know about the photo that could help someone locate my dad? We know it’s a photo of Jerry Lawler and that’s about it.

Over time, helpful information can get harder and harder to track down. My dad, as the rightsholder, couldn’t remember the name of the wrestling circuit they followed. Nor could he remember the company in Nashville that ran the circuit. He couldn’t remember the names of the other people who worked with him on the magazine, other than his business partners. He no longer had a copy of the magazine, nor could he remember what they even called it. A lawyer had drawn up the contract for the wrestlers’ consent forms, but he couldn’t remember who. Most likely, none of those contracts have survived. So, then, how is someone supposed to find out who took the photograph in order to ask my dad for permission to use it and give him credit? Even my dad, the photographer, doesn’t have a copy of the photo anymore.

Despite this, my dad’s main concerns are about attribution and economic enjoyment. That the photo is out there on the Internet doesn’t bother him. However, if anyone is being attributed to the photograph, he wants it to be him. If anyone is being paid for the photograph, he wants it to be him. Those are his rights as an author. If someone else is exercising them, they’re exercising them in his stead. Ultimately, they’re exercising surrogate intellectual property rights over his copyrighted, but orphaned, work.

Why it Matters

Artists, authors, painters, photographers, poets, and other creators all work really hard to make the works that we enjoy. By law, they’re entitled to reap the benefits of that hard work. We protect their hard work through copyright. When people disregard copyright, and infringe it, an author somewhere loses out on something to which he or she is legally entitled.

It can be difficult to respect these rights when it comes to the Internet. A work is often shared without attribution to the original author. After a while, that important context can disappear altogether.

In cases like my dad’s, it gets even more complicated. He took this photo when photography was completely analog. Unless each photo had his contact information somewhere on the front or back of the print, how’s someone to know who to credit or contact for reuse? Even if that information had been on the photo, would any of it still be current more than thirty years later? Nope.

The digital realm amplifies these issues exponentially. A photographer can attach metadata to a digital file that protects the context of the piece and includes the photographer, copyright and contact information, title, and other information. Even so, it’s remarkably easy (even unintentionally) to download a photo, strip it of its metadata, and upload it back to the internet. This very process creates an orphan copy of that digital work.

A Happy Ending (Yay for Research!)

During our conversation, my dad mentioned that Jerry Lawler had been “discovered” when he was working as a spray paint muralist in Memphis. As my dad remembered it, Jerry was making a mural when someone drove by and noticed how built he was. This man, Jackie Fargo, encouraged Jerry to take up wrestling.

I found it incredibly interesting that Jerry had originally been an artist himself. I thought I’d do a quick bit of research to see if any of Jerry’s murals had survived and made it on the internet. So I did a Google search for “Jerry Lawler mural.”

Look at what I found:

Come to find out, two artists, Nosey and Birdcap, have made their own Jerry Lawyer mural on a bridge in Memphis at Wiseacre Brewing. And it features my dad’s photo!

Finally, I know what you’re wondering, and yes: I did get permission from the photographer, Philip Murphy, to use his photo of the mural in this article.

Update: My dad has remembered the magazine name! He sent me an email saying, “now that I think about it, it was ‘Ring Side’.”

What a great “real life” Story! Thank you for sharing it Andrea! I love the way you explore difficult Law issues! So amazing!

Thanks, Ellen! It certainly helps that the photo itself is so entertaining… once I saw it, I thought how could I not write about it?!