Surrogate Rights Explained

Before reading this post, I recommend you first read “What are Surrogate IP Rights?”

Why “Surrogate”?

First, and as my colleague and friend Megan Rae Blakely pointed out, it’s important to define why I’m using the term “surrogate” and how it’s different from other copyright terms-of-art (like ancillary). There’s no use in reinventing the wheel if another term is out there that scoops up and captures what’s happening. However, be assured, there’s not.

Let’s take a look at the two terms as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary:

Surrogacy (sur¦ro|gate) is defined as “a substitute, especially a person deputizing for another in a specific role of office.”

Ancillary (an¦cil|lary) is defined as “(1) providing necessary support to the primary activities or operation of an organization, system, etc.” and “(1.1) in addition to something else, but not as important.”

Ancillary copyright has been used to describe rights that fall outside of traditional copyright protections, but resemble and are related to copyright and actually expand their protections. Creating ancillary copyright can be accomplished through legislation, a contract, or sometimes (wait for it) the terms and conditions found on a website. Sounds pretty relevant, right?

Well, what’s key to surrogacy is that all of the original intellectual property protections have expired. We can’t provide support to a primary copyright protection through ancillary copyright if the protection no longer exists. Instead of providing support, the rights being claimed serve as a substitute for the original right. This why using “surrogate” is more appropriate than using “ancillary”.

Why is this distinction important? Because of the glorious public domain: most of the time, the objects over which surrogate rights are being claimed are a part of the public domain and they should remain in the public domain. (Side note: other objects relevant to surrogate rights include orphan works, but that will be addressed in an orphan works series later to come.)

The Importance of Protecting the Public Domain

Okay, first, what is the public domain? An earlier post addresses this issue through a helpful example. To recap, the public domain is where intellectual property goes when protections expire. In theory, IP rights exist to incentivize innovation and creation. The idea is that when people know they will be entitled to the fruits of their labor, they think of and create more new things. IP rights ensure those creations are protected, but they only exist for a limited time. When that time is up, use of a work is fair game. Eventually everybody wins: the public pays to use a work during that time, but afterward the public gains the right to reuse that work unencumbered.

There are also other items in the public domain that never received copyright protections in the first place. Some things, by law, are automatically deemed public domain. Others have had those protections voluntarily waived by their authors (thanks y’all, that was thoughtful).

So, the public domain is basically cultural goods heaven. Anyone can reuse an item in the public domain without first seeking permission of the author or creator. Further, they don’t need to compensate the author, nor do they even really need to credit the author (though it’s always good practice). In general, intellectual property-related protections just do not apply to items in the public domain.

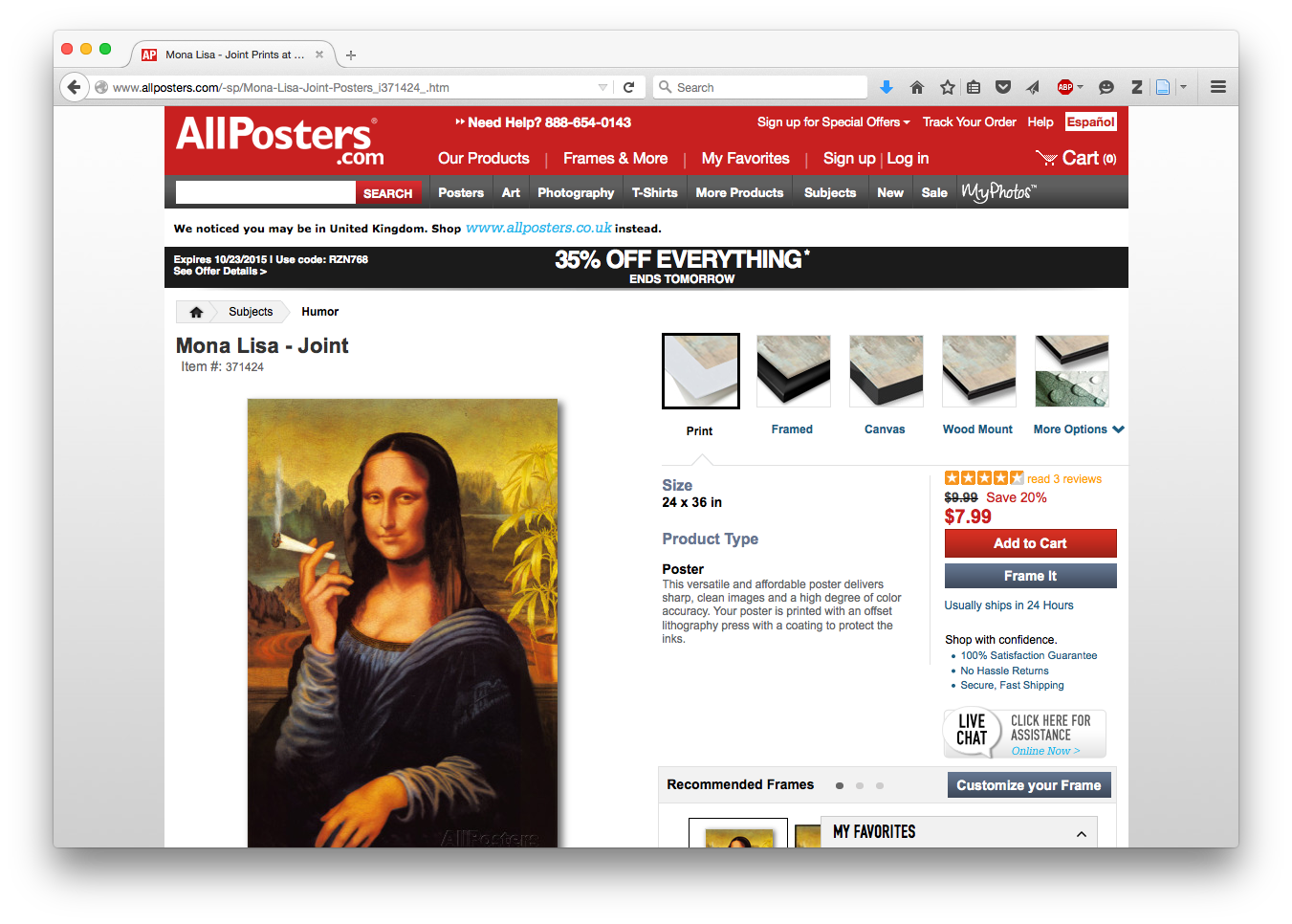

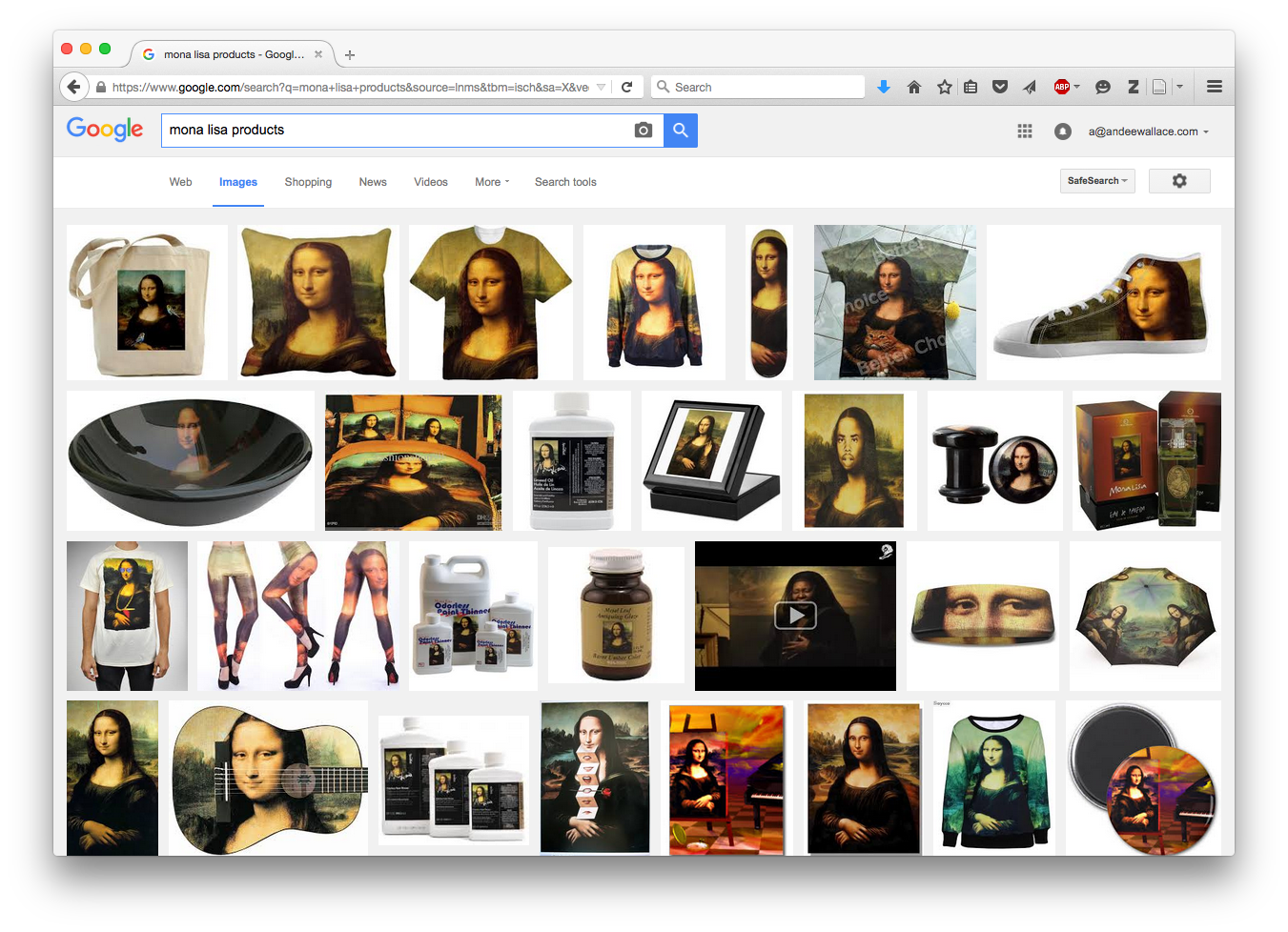

What does this all mean? It means you can finally take the Mona Lisa and make her smoke a doobie, print it poster size, and put it up in your dorm room.

What’s better is that you can turn that gorgeous work of art into a poster and sell it online.

But why stop with a poster? You can have Mona Lisa on everything and you can sell it too: coffee, leggings, a watch, a bag, pillows, perfume, laundry detergent (???), and so much more. The sky is the limit, the possibilities are endless, and you owe it all to the public domain (and Leonardo da Vinci, to be fair).

Google image search for “mona lisa products”: https://www.google.com/search?q=mona+lisa+products&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0CAcQ_AUoAWoVChMIxebZuLvWyAIVwscUCh14uQ-8&biw=1384&bih=835&dpr=0.9

Works Created Before Copyright and the Irony of the Public Domain

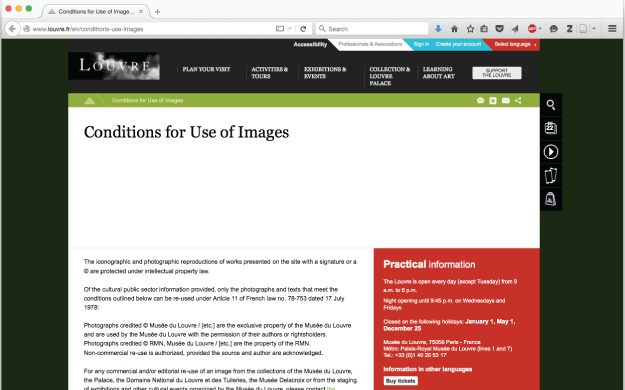

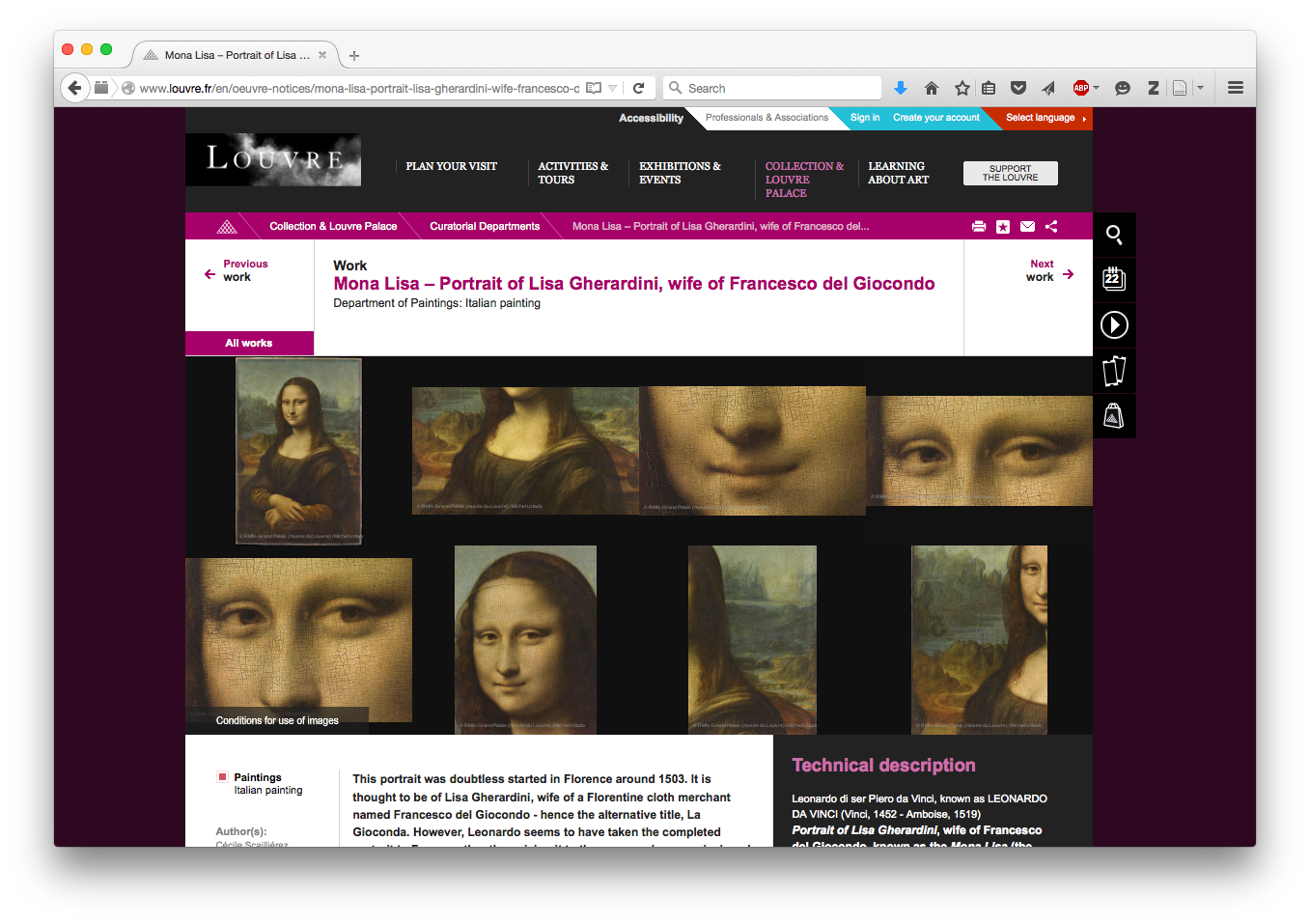

You can find various (allegedly) non-restricted digital versions of the Mona Lisa online, but that’s not always the case with every work in the public domain. Sometimes you have to go to the cultural institution for an image. If you go to the Louvre, they’re going to ask for some cash. This is because they (or the company that digitizes the object) claim copyright in the image.

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/mona-lisa-portrait-lisa-gherardini-wife-francesco-del-giocondo

See that there in the corner? It’s on every image.

Here’s a fun fact: Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa before copyright even existed. Herein lies another irony: these IP rights are being claimed over objects that the author himself never had the pleasure of invoking.

In fact, many of the objects in collections, like ancient pottery, coins, jewelry, and weaponry, were made well before copyright ever existed and were never intended for copyright protections in the first place. Some of these items, if made today, would still be ineligible for IP protections. However, once they get digitized, a cultural institution claims a copyright over the image and thereby restricts access to that public domain work.

It’s not like you could take an ancient figurine and bedazzle it and say it’s your right because it’s in the public domain. A cultural institution may have a property right in the object, but not an intellectual property right. The only way to really make use of such objects is through using a digital reproduction—like a digital image that itself is a surrogate for the source item.

Why does this matter?

Restricting access to those digital versions undermines the rationale of the public domain and it prevents current and future generations from creating new cultural goods and knowledge. Not only does this undermine the rationale of copyright expiration and the public domain, but it harms the public domain by restricting access to works intended to be used for cultural reproduction.