Surrogate IP Rights in Social Media: Ugly Renaissance Babies

Who doesn’t love a good ugly Renaissance baby?

First, a bit of background: during the Renaissance, artists became more interested in depicting the human body more accurately and realistically than they had in the Middle Ages. Much of this came down to getting the proportions right (side note: they wanted them to look like little men for philosophical reasons). And, much to our delight today, it took a bit of time before they sorted out the best proportions for babies.

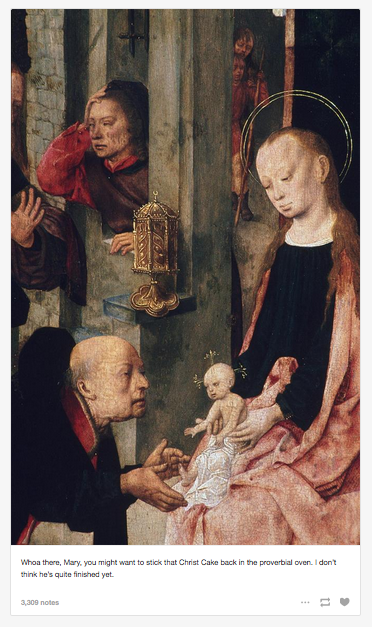

To illustrate, an adult’s body is about 8 adult heads tall. By contrast, a baby’s body is about 4 baby heads tall. What does it all mean? Well, when you paint a baby with adult proportions, it ends up looking something like this, and it’s kind of glorious:

http://uglyrenaissancebabies.tumblr.com/post/22322571058/maerten-van-heemkerck-goddamn-you-could-grate

So, basically, NOT like a baby at all. In fact, both fascinating and terrifying… and I can’t look away.

Now for the surrogate IP rights stuff.

Renaissance paintings are in the public domain—but whether digital images of Renaissance paintings are in the public domain depends on whether or not someone has claimed a copyright over the images. This could be a cultural institution or a museum visitor snapping a shot with an iPhone. For simplicity’s sake, let’s just assume no one has claimed copyright and that the images are also in the public domain. This means I’m free to use the images to create some new fun thing about Renaissance paintings. Suppose that thing is a Tumblr or Twitter account that showcases all my favorite ugly Renaissance babies. Well, too late, because maybe you guessed it already, but it already exists.

Without further ado, let me introduce you to the Ugly Renaissance Babies Tumblr, where users submit their favorite ugly renaissance baby with a witty caption:

Admittedly, some of them crack a smile. But where do users get the images they submit? Are they violating any terms and conditions by using them in this way? Even if the photos aren’t copyrighted, institutions usually require attribution to the artist and the host cultural institution as a condition of use. They might also say you can’t crop or edit the image in any way. Why all the rules? Well, it’s important. Someone might come across the painting, want to use it, and need to know where to find it. Also, not including this information creates another problem. It creates an orphan, meaning we don’t know whether it’s in copyright or who the artist is—whether that’s the original artist, a photographer, or the cultural institution that claims copyright over the image.

Okay, so I tried to figure out just how hard it is to find that information out myself using the original image above. The first thing you would do is look at the Ugly Renaissance Babies entry to see if any of this information has been mentioned. Good news, for this piece it has:

But it’s just the artist and not the title of the painting. We still don’t know what it’s called. How can we find out? First, run a Google search for Maerten van Heemkerck to see if the painting comes up:

Hmmm, it’s not there. I still can upload the image to a Google Image search to see if it returns anything. So I did, and here’s what came up:

Based on the image, Google’s “best guess for this image” is none other than Ugly Renaissance Babies. Other returns include BuzzFeed articles and Pinterest pages. All are popular social media sites, and not actually helpful.

I clicked on the BuzzFeed article to see if that article cited the painting’s title or cultural institution.

Nope. Instead, the article cites Ugly Renaissance Babies as the source and includes no information about the artwork, even where that information was included on the Ugly Renaissance Babies post:

This got me thinking: how many Ugly Renaissance Babies entries actually include the artist or title, or even cite the source? I’ll tell you (yes, I went through them all).

Of the 310 entries it goes something like this:

- 221 posts include the artist and title

- 7 posts include only the artist

- 6 posts include only the title

- 76 include no information on the artwork

Only 4 of those 310 entries actually include the institution where the work is held. It’s obvious that several images have been cropped. Some do include the date of creation. (I plan to go through a sample of these and make sure the citations are even correct. If not, that adds a whole other issue of misinformation to the mix.)

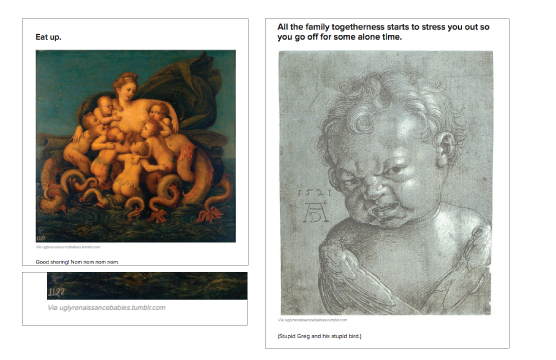

During my review, I found a bunch of other fun and interesting entries. Here we go:

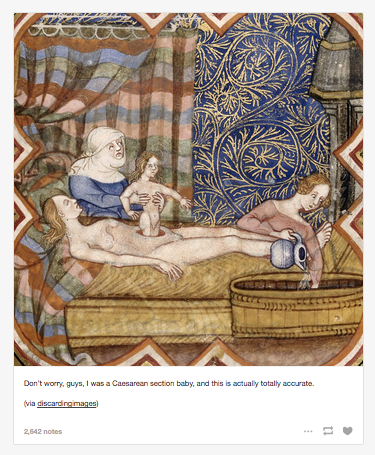

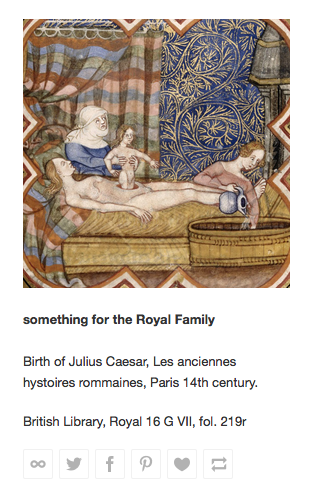

Interesting post #1

This entry lists “discardingimages” as the source, but it doesn’t list the artist, institution or any other information.

Funny thing, Discarding Images is a Tumblr (and has a Twitter) that uploads public domain content with all of that appropriate citation stuff for you. Here’s the same entry on discardingimages:

Why not just copy and paste the information?

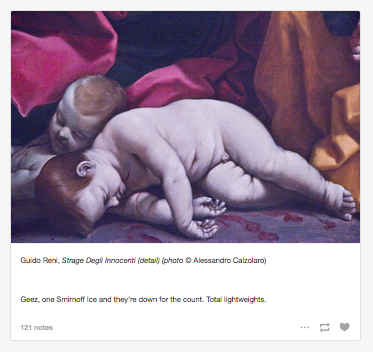

Interesting post #2

Look closely, this entry includes the © holder for the photo.

I searched online for the artwork and found out through Wikipedia that the painting is at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna. The museum’s website doesn’t make images available, so it’s not clear whether this image was taken at the museum and submitted by Alessandro Calzolaro and he’s claiming the copyright himself, or the detail comes from an image taken by Alessandro and submitted by someone else. Anyway, it’s the only entry out of 310 others that has any copyright claim on it (stroking chin like a villain emoji).

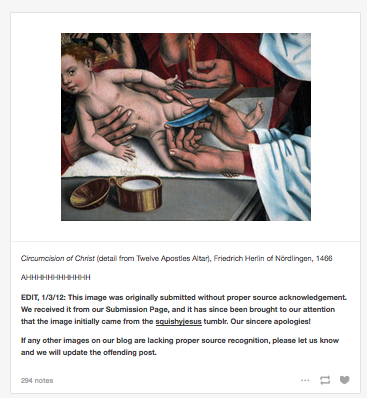

Interesting post #3

Let’s read this “EDIT” together:

“This image was originally submitted without proper source acknowledgement. We received it from our Submission Page, and it has since been brought to our attention that the image initially came from squishyjesus tumblr. Our sincere apologies!

If any other images on our blog are lacking proper source recognition, please let us know and we will update the offending post.”

So, this entry has an edit, because Ugly Renaissance Babies originally failed to attribute the person who submitted it. It’s not clear whether the someone managing the page brought this to their attention, or whether the submitter reached out and let them know that “the squishyjesus Tumblr” hadn’t received credit. Regardless, it illustrates how important attribution is to the people who want to be credited for their work (even on Ugly Renaissance Babies), and I just find it a tad bit ironic (winky face emoji).

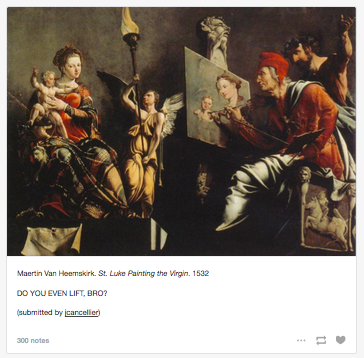

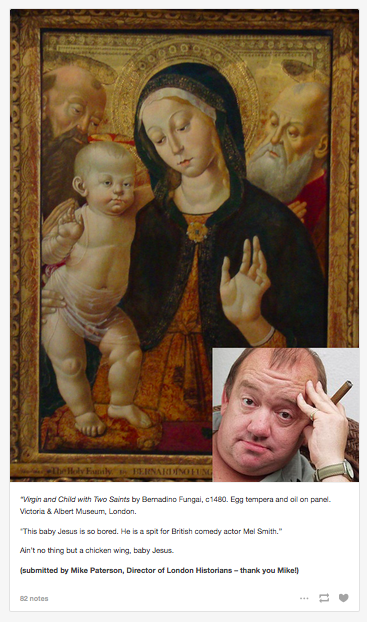

Interesting post #4:

Wait! I found the painting that I was looking for!

Someone submitted it for a different entry! Now I know that the other, smaller painting was actually a cropped detail from this larger painting. And now I know the title, rather than just the artist. Thanks for unintentionally clearing that up Ugly Renaissance Babies!

Interesting post #5:

This one might be my favorite.

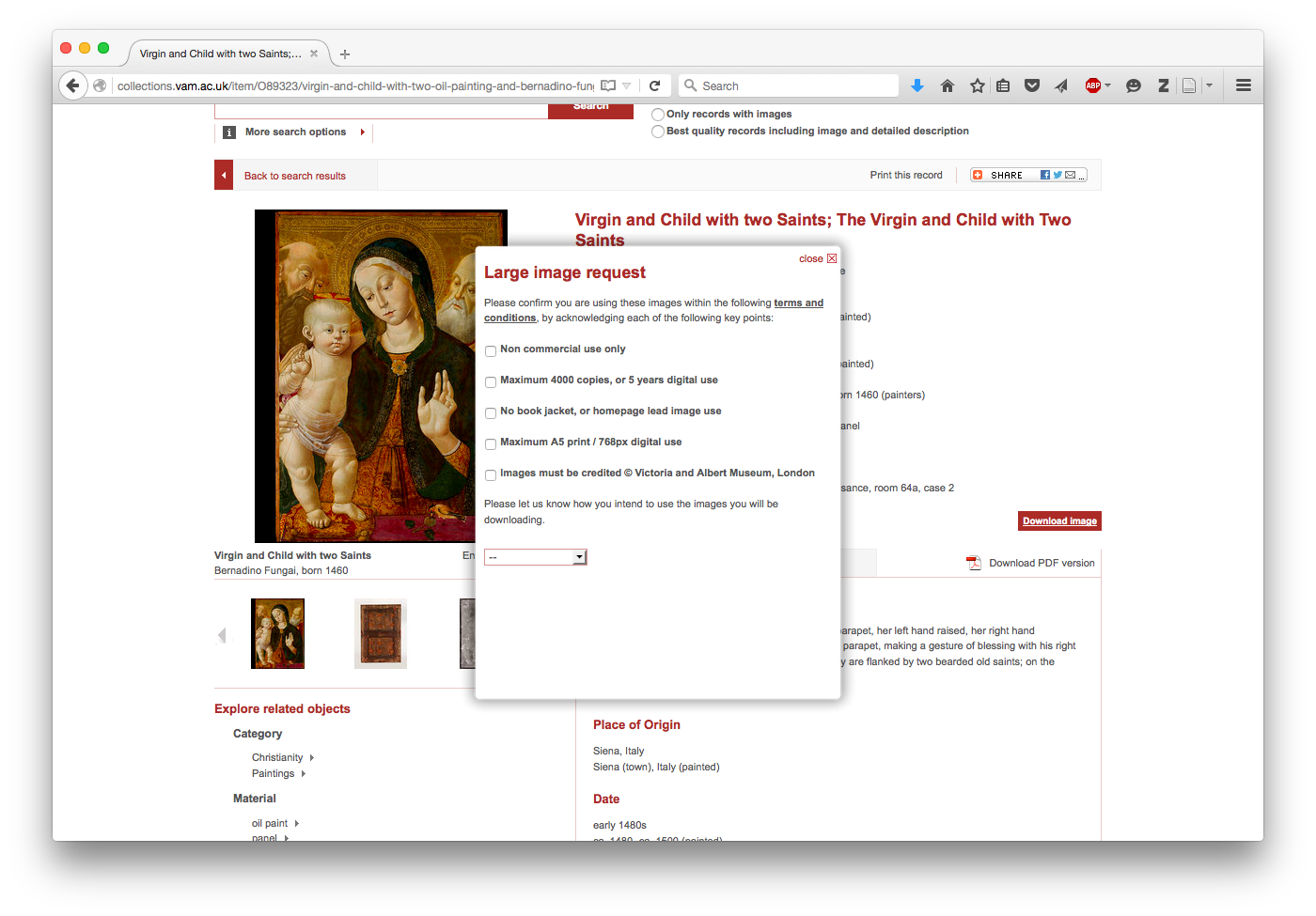

First, the citation is great and very thorough, but it fails to include one very important detail: this image might be copyrighted by the Victoria & Albert Museum, London and, if so, should be credited as such. By failing to include this in the citation, the use violates the V&A’s copyright policy: “For any V&A Content use the following copyright credit line must be used, unless otherwise stated: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London”.

Second, there’s a photo imposed in the bottom right-hand corner. Doing this also violates the V&A’s copyright policy, which protects the integrity of the image from this type of alteration.

However… the submitted image doesn’t actually look like the image made available by V&A. The lighting is different; there’s a gold frame around it; it’s cropped differently. So, this brings up another point: the image came from somewhere else and we don’t know where. Maybe the submitter took this image himself while visiting the V&A. If that’s the case, it’s totally appropriate for him to use this without any copyright acknowledgement to V&A. Instead, the submitter would hold the copyright. Still, if he doesn’t state this or disclaim copyright, this image could eventually become an orphan as it gets reused and redistributed around the Internet… (is your mind blowing yet?).

And, finally, the submitter is the Director of London Historians. It’s fantastic to know that historians find this site entertaining and submit entries. But not everyone feels the same way about these types of social media sites…

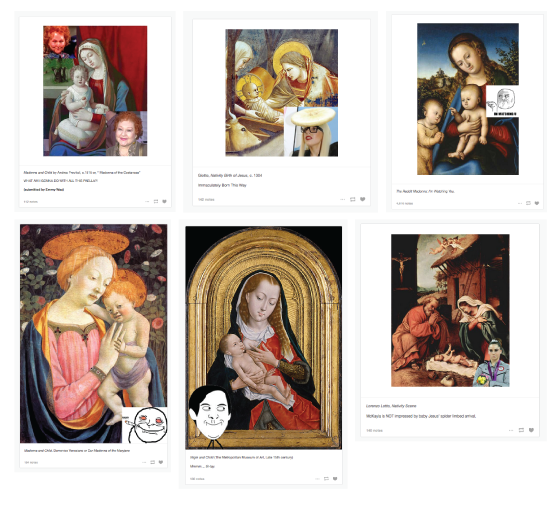

Back to the alteration point: assuming the director took this image himself, alteration of the image is fine as long as he is the one who altered his image. But this isn’t the only image that’s been altered, nor is it clear whether these submitters have violated any terms by downloading, altering, and submitting them:

So, then, what’s the big deal? After all, if these artworks are supposed to be public domain, shouldn’t people be able to use them however they like, regardless of how they’re used? I think so. But I also think it’s really important to clearly cite where they came from and who made them in case someone out there needs (or even just wants) to know. Artists went to a lot of trouble to paint these artworks. Professionals devote their entire careers to studying and educating others about them. Cultural institutions go to a lot of trouble to preserve these artworks and make the works and the information about them available, usually through the institution’s website.

So, then, what’s the big deal? After all, if these artworks are supposed to be public domain, shouldn’t people be able to use them however they like, regardless of how they’re used? I think so. But I also think it’s really important to clearly cite where they came from and who made them in case someone out there needs (or even just wants) to know. Artists went to a lot of trouble to paint these artworks. Professionals devote their entire careers to studying and educating others about them. Cultural institutions go to a lot of trouble to preserve these artworks and make the works and the information about them available, usually through the institution’s website.

Once an artwork’s context is stripped away, it can be really hard to try to find out where, or even what, that artwork is. This is especially true when the image becomes cropped or altered in a way that makes it hard to connect it to the original work. And, regardless of where someone gets an image or whether they take it themselves, everyone should still cite to the original artwork, its artist, and its cultural institution. It’s just good practice.

Ultimately, the Internet is supposed to make things easier, not harder. When we don’t properly cite the things we disseminate on the Internet, information becomes diluted instead of being made more accessible.